- Research

- Open access

- Published:

Risk factors associated with newly diagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: a retrospective case-control study

BMC Psychiatry volume 23, Article number: 870 (2023)

Abstract

Background

Knowledge of risk factors for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may facilitate early diagnosis; however, studies examining a broad range of potential risk factors for ADHD in adults are limited. This study aimed to identify risk factors associated with newly diagnosed ADHD among adults in the United States (US).

Methods

Eligible adults from the IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus database (10/01/2015-09/30/2021) were classified into the ADHD cohort if they had ≥ 2 ADHD diagnoses (index date: first ADHD diagnosis) and into the non-ADHD cohort if they had no observed ADHD diagnosis (index date: random date) with a 1:3 case-to-control ratio. Risk factors for newly diagnosed ADHD were assessed during the 12-month baseline period; logistic regression with stepwise variable selection was used to assess statistically significant association. The combined impact of selected risk factors was explored using common patient profiles.

Results

A total of 337,034 patients were included in the ADHD cohort (mean age 35.2 years; 54.5% female) and 1,011,102 in the non-ADHD cohort (mean age 44.0 years; 52.4% female). During the baseline period, the most frequent mental health comorbidities in the ADHD and non-ADHD cohorts were anxiety disorders (34.4% and 11.1%) and depressive disorders (27.9% and 7.8%). Accordingly, a higher proportion of patients in the ADHD cohort received antianxiety agents (20.6% and 8.3%) and antidepressants (40.9% and 15.8%). Key risk factors associated with a significantly increased probability of ADHD included the number of mental health comorbidities (odds ratio [OR] for 1 comorbidity: 1.41; ≥2 comorbidities: 1.45), along with certain mental health comorbidities (e.g., feeding and eating disorders [OR: 1.88], bipolar disorders [OR: 1.50], depressive disorders [OR: 1.37], trauma- and stressor-related disorders [OR: 1.27], anxiety disorders [OR: 1.24]), use of antidepressants (OR: 1.87) and antianxiety agents (OR: 1.40), and having ≥ 1 psychotherapy visit (OR: 1.70), ≥ 1 specialist visit (OR: 1.30), and ≥ 10 outpatient visits (OR: 1.51) (all p < 0.05). The predicted risk of ADHD for patients with treated anxiety and depressive disorders was 81.9%.

Conclusions

Mental health comorbidities and related treatments are significantly associated with newly diagnosed ADHD in US adults. Screening for patients with risk factors for ADHD may allow early diagnosis and appropriate management.

Background

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a debilitating neurodevelopmental condition with an estimated prevalence of 4.4% among adults in the United States (US) [1]. ADHD is traditionally perceived as a childhood disorder [2]; hence, underdiagnosis, delayed diagnosis, and undertreatment of ADHD are believed to be common among adults [3, 4].

The diagnostic challenges of ADHD are partially attributable to the frequent comorbid mental disorders [5, 6]. Certain mental health comorbidities, such as anxiety and depressive disorders, share overlapping symptoms with ADHD [7, 8], potentially leading to misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis. Studies have suggested that about one-fifth of adults seeking psychiatric services and reporting for other mental health conditions were later found to have ADHD [9,10,11]. The World Health Organization Mental Health Survey has also reported that among US adults with ADHD identified through diagnostic interviews, approximately half had received some form of treatment for their emotional or behavioral problems in the past year, but only 13.2% were treated specifically for ADHD [12]. Clinicians’ lack of awareness or training on adult ADHD may also hinder ADHD diagnosis [4]. A US medical record-based study found that 56% of adults with ADHD had not received a prior diagnosis of the condition despite complaining about ADHD symptoms to other healthcare professionals in the past [13]. Other reasons adding to the diagnostic challenge of ADHD in adults may include patient’s fear of stigma and masking behaviors developed over the years [4, 14].

ADHD is associated with a wide range of psychosocial, functional, and occupational problems in adults [15]. A delay in diagnosis, or undiagnosed and ultimately untreated ADHD, may lead to poor clinical and functional outcomes even if comorbidities are treated [16]. Conversely, early identification of ADHD may allow better symptom management and improve patient functioning and quality of life. To facilitate diagnosis, risk factors are commonly used to predict disease development and aid clinicians to identify at-risk patients [17]. However, there is a paucity of large studies examining a broad range of potential risk factors for an ADHD diagnosis in adults. Prior studies have reported certain patient characteristics, such as presence of anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, sleep impairments, eating disorders, and childhood illnesses or health events (e.g., obesity, head injuries, infections) that may be associated with ADHD [18,19,20,21,22,23]. Yet, most of these studies have examined a single or a few factors, and many were conducted in pediatric ADHD populations primarily outside of the US.

Knowledge on patient characteristics associated with a higher risk of ADHD in adults and the patient journey prior to a clinical ADHD diagnosis may facilitate early diagnosis and the provision of appropriate management. The current study was conducted to identify risk factors for newly diagnosed ADHD in adult patients using a large claims database in the US. The potential utility of the results was also demonstrated through exploring the combined impact of selected risk factors on ADHD risk prediction using fictitious common patient profiles.

Methods

Data source

Data from the IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus (IQVIA) database covering the period of October 1, 2015, to September 30, 2021, were used. The IQVIA database contains integrated claims data of over 190 million beneficiaries across the US and includes information on inpatient and outpatient diagnoses and procedures, prescription fills, patients’ pharmacy and medical benefits, inpatient stays, and provider details. Additional data elements encompass dates of service, demographic variables, plan type, payer type, and start and stop dates of health plan enrollment. Data are de-identified and comply with the patient requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA); therefore, no review by an institutional review board nor informed consent was required per Title 45 of CFR, Part 46.101(b)(4) [24].

Study design and patient populations

A retrospective case-control study design was used. Eligible adults were classified into two cohorts based on the presence of ADHD diagnoses (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] F90.x): the ADHD cohort comprised patients with ≥ 2 ADHD diagnoses recorded on a medical claim on distinct dates at any time during their continuous health plan enrollment; and the non-ADHD cohort comprised patients without any ADHD diagnoses recorded on a medical claim at any time during their continuous health plan enrollment. To account for large differences in sample size and to retain statistical power, a 1:3 case-to-control ratio was used. Specifically, eligible patients were randomly selected into the non-ADHD cohort such that the total number of patients in the non-ADHD cohort was three times that of the ADHD cohort.

The index date was defined as the first observed ADHD diagnosis among the ADHD cohort and a randomly selected date among the non-ADHD cohort. To allow sufficient time to capture potential risk factors for ADHD, patients were required to have ≥ 12 months of continuous health plan enrollment prior to the index date. The baseline period was defined as the 12 months pre-index.

Study measures and outcomes

Patient characteristics and potential risk factors for newly diagnosed ADHD were assessed during the baseline period for each cohort, separately. Potential risk factors considered in this study were identified through a targeted literature review and observable variables in the data and included demographic characteristics (i.e., age, sex, regions of residence, calendar year of index date), clinical characteristics (i.e., physical and mental health comorbidities), pharmacological treatments (i.e., medications for common ADHD comorbidities), healthcare resource utilization (i.e., number of psychotherapy, inpatient, emergency room, outpatient, and specialist [psychiatrist, neurologist] visits). Risk factors for ADHD in this study were identified from potential risk factors that had statistically significant association with newly diagnosed ADHD, as described in the next section.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline patient characteristics and potential risk factors for newly diagnosed ADHD. Means, medians, and standard deviations (SDs) were reported for continuous variables; frequency counts and percentages were reported for categorical variables.

Univariate statistics were used to compare potential risk factors between the ADHD and non-ADHD cohorts. The magnitude of the difference between cohorts was assessed by calculating the standardized differences (std. diff.) for both continuous and categorical variables.

Logistic regression model with stepwise variable selection was used to assess statistically significant association between potential risk factors and ADHD diagnosis. Potential risk factors were eligible for inclusion in the logistic regression based on their univariate association with ADHD diagnosis (i.e., std. diff. >0.10). Potential risk factors presented in < 0.5% of the sample were discarded. Variables included in the last iteration of the stepwise selection process were considered as risk factors of the study outcome. The association between risk factors and ADHD diagnosis were reported as odds ratios (ORs) along with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values.

To facilitate the interpretation of the regression analyses, the predicted risk of ADHD based on regression coefficient estimates was evaluated for six fictitious common patient profiles corresponding to patients who harbor selected combinations of ADHD risk factors. This exploratory analysis allowed for the estimation of how the risk of having ADHD would vary had the same person had additional risk factors but otherwise the same characteristics.

Results

Patient characteristics and potential risk factors

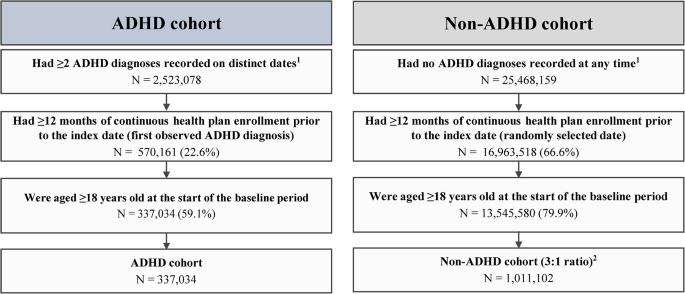

The total sample comprised 1,348,136 patients, including 337,034 in the ADHD cohort and 1,011,102 in the non-ADHD cohort (Fig. 1). Table 1 presents the patient characteristics and potential risk factors (i.e., characteristics with a std. diff. >0.10) by cohort.

Sample selection flowchart. ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ICD-10-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification

Notes:

1ADHD was defined as ICD-10-CM codes: F90.x

2Eligible patients were randomly selected into the non-ADHD cohort such that the total number of patients in the non-ADHD cohort is 3 times that of the ADHD cohort to account for large differences in sample size

Demographic characteristics

As of index date, the ADHD cohort was younger than the non-ADHD cohort (mean age: 35.2 and 44.0 years; std. diff. = 0.68). In both cohorts, slightly over half of the patients were female (54.5% and 52.4%; std. diff. = 0.04), and the South was the most represented region (48.7% and 42.5%; std. diff. = 0.13).

Clinical characteristics

During the baseline period, the most frequent physical comorbidities in the ADHD and non-ADHD cohorts were hypertension (12.4% and 21.3%; std. diff. = 0.24), obesity (10.0% and 9.4%; std. diff. = 0.02), and chronic pulmonary disease (9.0% and 7.2%; std. diff. = 0.07).

A lower proportion of patients had no mental health comorbidities in the ADHD cohort than the non-ADHD cohort (42.0% and 70.8%; std. diff. = 0.61). The mean ± SD number of mental health comorbidities was 1.2 ± 1.4 in the ADHD cohort and 0.5 ± 0.9 in the non-ADHD cohort (std. diff. = 0.65). The most frequent mental health comorbidities in the ADHD and non-ADHD cohorts were anxiety disorders (34.4% and 11.1%; std. diff. = 0.58), depressive disorders (27.9% and 7.8%; std. diff. = 0.54), sleep-wake disorders (13.2% and 7.7%; std. diff. = 0.18), trauma- and stressor-related disorders (12.4% and 3.4%; std. diff. = 0.34), and substance-related and addictive disorders (9.4% and 5.0%; std. diff. = 0.17).

Pharmacological treatments

A higher proportion of patients in the ADHD than the non-ADHD cohort received antidepressants (40.9% and 15.8%; std. diff. = 0.58), antianxiety agents (20.6% and 8.3%; std. diff. = 0.36), anticonvulsants (16.1% and 6.8%; std. diff. = 0.29), and antipsychotics (7.2% and 1.5%; std. diff. = 0.28).

Healthcare resource utilization

The ADHD cohort, relative to the non-ADHD cohort, had generally higher mean ± SD rates of healthcare resource utilization, including more psychotherapy visits (2.9 ± 8.8 and 0.6 ± 4.0; std. diff. = 0.34), emergency room visits (0.6 ± 1.7 and 0.4 ± 1.2; std. diff. = 0.14), outpatient visits (12.7 ± 16.5 and 8.3 ± 12.4; std. diff. = 0.30), and specialist visits (1.0 ± 4.0 and 0.2 ± 1.8; std. diff. = 0.24); the number of inpatient visits were similar between cohorts (0.1 ± 0.4 and 0.1 ± 0.3; std. diff. = 0.04).

Association between risk factors and ADHD diagnosis

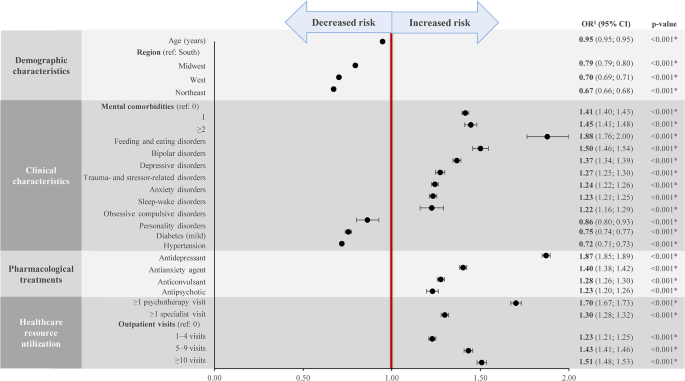

The risk factors with a significant association with an ADHD diagnosis are presented in Fig. 2. Demographically, being younger and living in the South were risk factors for having an ADHD diagnosis (OR for age: 0.95; OR for region of residence using South as a reference: Midwest, 0.79; West, 0.70; Northwest, 0.67; all p < 0.05).

Other key risk factors associated with a significantly increased probability of having an ADHD diagnosis included the number of mental health comorbidities (OR for 1 comorbidity: 1.41; ≥2 comorbidities: 1.45); certain mental health comorbidities, including feeding and eating disorders (OR: 1.88), bipolar disorders (OR: 1.50), depressive disorders (OR: 1.37), trauma- and stressor-related disorders (OR: 1.27), anxiety disorders (OR: 1.24), sleep-wake disorders (OR: 1.23), and obsessive compulsive disorders (OR: 1.22); use of antidepressants (OR: 1.87) and antianxiety agents (OR: 1.40); and having ≥ 1 psychotherapy visit (OR: 1.70), ≥ 1 specialist visit (OR: 1.30), and ≥ 10 outpatient visits (OR: 1.51) (all p < 0.05).

Predicted risk of ADHD for patient profiles with selected risk factors

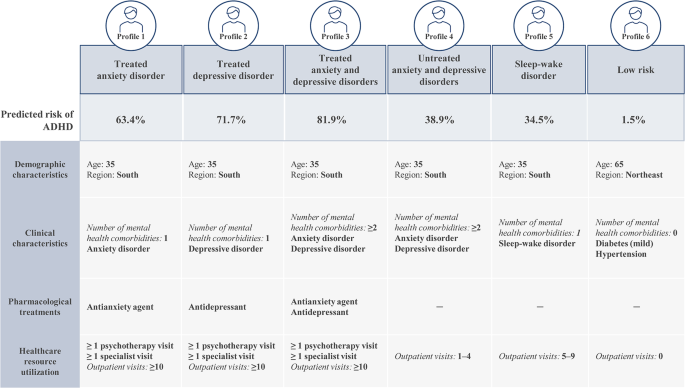

Selected risk factors identified from the logistic regression analyses were used to create fictitious common patient profiles to demonstrate their combined impact on the predicted risk of having an ADHD diagnosis (Fig. 3). Five of the six profiles correspond to patients with the same demographic characteristics (i.e., aged 35 years and living in the South) but vary in terms of the number (i.e., 1 or ≥ 2) and types of mental health comorbidities (i.e., anxiety disorder and/or depressive disorder), the pharmacological treatment received (i.e., antianxiety and/or antidepressant agent, or no treatment), and the level of healthcare resource utilization (i.e., number of psychotherapy, specialist, and outpatient visits). The remaining profile corresponds to low-risk patients with no relevant risk factors for ADHD.

Based on these patient profiles, the predicted risk of ADHD was the highest among patients with treated anxiety and depressive disorders (profile 3). More specifically, a patient presenting with the characteristics described in this profile would have an 81.9% likelihood of being diagnosed with ADHD in the coming year. The profile with the next highest predicted risk of ADHD was patients with treated depressive disorder (profile 2; 71.7%), followed by patients with treated anxiety disorder (profile 1; 63.4%). Profiles corresponding to a moderate predicted risk of ADHD included patients with untreated anxiety and depressive disorders (profile 4; 38.9%) and patients with sleep-wake disorder (profile 5; 34.5%). The predicted risk for ADHD among low-risk patients (profile 6) was 1.5%.

Discussion

This large retrospective case-control study has identified a broad range of risk factors associated with ADHD in adults and quantified the added likelihood of an ADHD diagnosis contributed by each factor. Certain mental health comorbidities and their associated treatments and care were found to be significantly associated with newly diagnosed ADHD in adults. Specifically, the presence of common mental health comorbidities of ADHD such as anxiety and depressive disorders was associated with 24% and 37% increased risk of having an ADHD diagnosis, respectively. The use of pharmacological treatments for these conditions such as antianxiety agents and antidepressants was associated with an increased risk of having an ADHD diagnosis of 40% and 87%, respectively; having at least one prior psychotherapy visit was also associated with a 70% increased risk. Demographically, being younger and living in the South were found to be risk factors for having an ADHD diagnosis. The combined impact of selected risk factors on the predicted ADHD risk was explored through specific patient profiles, which demonstrated how the findings may be interpreted in clinical settings. The presence of a combination of risk factors may suggest that a patient is at a high risk of having undiagnosed ADHD and signify the need for further assessments. Collectively, findings of this study have extended our understanding on the patient path to ADHD diagnosis as well as the characteristics and clinical events that could suggest undiagnosed ADHD in adults.

Most prior studies examining characteristics associated with ADHD have focused on a single or a few factors, and many were conducted in pediatric populations [18,19,20,21,22,23]. Nonetheless, the risk factors for ADHD identified in the current study are largely aligned with the literature. For instance, among prior research in adults, a multicenter patient register study found that at the time of first ADHD diagnosis, mental health comorbidities were present in two-thirds of the patients; patients on average presented with 2.4 comorbidities, with the most common comorbidities being substance use disorders, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and personality disorders [6]. Another study among adult members of two large managed healthcare plans found that compared with individuals without ADHD, those screened positive for ADHD through a telephone survey but had no documented ADHD diagnosis (i.e., the undiagnosed group) had significantly higher rates of mental health comorbidities (e.g., anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder) and were more likely to receive medications for a mental health condition [25]. In line with these findings, the current exploratory patient profile analyses also suggest that patients with more mental health comorbidities and have received the associated pharmacological treatments and care are at a higher risk of having undiagnosed ADHD than those with fewer or untreated mental health comorbidities.

The current study also found that an overall higher healthcare resource utilization was a characteristic associated with newly diagnosed ADHD among adult patients. A potential interpretation of this finding is that an individual who experienced ADHD-related symptoms might visit a psychologist or physician frequently to seek help for the symptoms; thus, a high level of prior healthcare resource utilization may be a sign that an individual could have undiagnosed ADHD. Clinical judgement should be applied to determine whether further evaluation for ADHD is needed on a case-by-case basis considering the presence of other high-risk characteristics.

The diagnosis of ADHD can be challenging, particularly among adults [2, 3]. The current study suggests that information on patient characteristics, such as the presence of mental health comorbidities and healthcare resource utilization history, may be used to aid clinicians identify adult patients at risk of ADHD and minimize missed opportunity to provide a timely diagnosis of ADHD and the proper care. Notably, underdiagnosis or a delayed diagnosis of ADHD leads to undertreatment and can adversely affect patients’ occupational achievements, diminish self-esteem, and hamper interpersonal relationships, considerably reducing the quality of life [8]. ADHD in adults has also been shown to be associated with approximately $123 billion total societal excess costs in the US [26]. Consequently, early detection and treatment of ADHD may have the potential to alleviate the large patient and societal burden associated with the condition.

It is worth mentioning that causes for ADHD is multifactorial, and multiple risk factors may contribute to the risk of having ADHD [15]. Some risk factors in the literature (e.g., genetics and environmental factors [27, 28]) are not available in claims data, and these factors are important to consider when establishing an ADHD diagnosis. Nonetheless, the risk factors identified in this study were generated based on a large sample size (over 1.3 million adults), and as exemplified by the exploratory patient profiles, the presence of multiple risk factors was associated with an overall higher risk of having undiagnosed ADHD. Together, these findings would help inform clinicians on the types of high-risk patient profiles that should raise a red flag for potential ADHD and prompt further clinical assessments, such as family psychiatric history and diagnostic interviews. As such, findings of this study may facilitate early diagnosis and appropriate management of ADHD among adults, which may in turn improve patient outcomes.

The findings of the current study should be considered in light of certain limitations inherent to retrospective databases using claims data, including the risk of data omissions, coding errors, and the presence of rule-out diagnosis. Nonetheless, while few studies specifically assessed the validity of ICD-10-CM codes for ADHD diagnoses in claims data, literature evidence has suggested high accuracy of ICD-9-CM codes in identifying neurodevelopmental disorders, including ADHD, and a good correspondence between the ICD-9 and − 10 codes is expected [29, 30]. Furthermore, ICD codes have been widely used in the literature to identify ADHD diagnoses in claims-based analyses [31,32,33]. Meanwhile, as the study included commercially insured patients, the sample may not be representative of the entire ADHD population in the US. Furthermore, potential risk factors were limited to information available in health insurance claims data only, which may lack relevant information related to ADHD, such as presence of childhood ADHD, family history, or environmental factors. In addition, some characteristics may interact with multiple variables such that their association with an ADHD diagnosis may already be captured by other variables; as such, a characteristic with an OR of less than 1 should not be interpreted as having a protective effect against an ADHD diagnosis but rather that the characteristic alone may be insufficient to prompt screening for ADHD. Lastly, findings from this retrospective observational analysis should be interpreted as measures of association; no causal inference can be drawn.

Conclusions

This large retrospective case-control study found that mental health comorbidities and related treatments and care are significantly associated with newly diagnosed ADHD in US adults. The presence of a combination of risk factors may suggest that a patient is at a high risk of having undiagnosed ADHD. The results of this study provide insights on the path to ADHD diagnosis and may aid clinicians identify at-risk patients for screening, which may facilitate early diagnosis and appropriate management of ADHD.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from IQVIA but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the corresponding author (email: Rebecca.Bungay@analysisgroup.com) upon reasonable request and with permission of IQVIA.

Abbreviations

- ADHD:

-

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- HIPAA:

-

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

- ICD-10-CM:

-

International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- Std. diff:

-

Standardized difference

- US:

-

United States

References

Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, Biederman J, Conners CK, Demler O, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):716–23.

Weibel S, Menard O, Ionita A, Boumendjel M, Cabelguen C, Kraemer C, et al. Practical considerations for the evaluation and management of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults. Encephale. 2020;46(1):30–40.

Ginsberg Y, Quintero J, Anand E, Casillas M, Upadhyaya HP. Underdiagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adult patients: a review of the literature. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(3).

Prakash J, Chatterjee K, Guha S, Srivastava K, Chauhan VS. Adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: from clinical reality toward conceptual clarity. Ind Psychiatry J. 2021;30(1):23–8.

Kooij JJ, Huss M, Asherson P, Akehurst R, Beusterien K, French A, et al. Distinguishing comorbidity and successful management of adult ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2012;16(5 Suppl):3S–19S.

Pineiro-Dieguez B, Balanza-Martinez V, Garcia-Garcia P, Soler-Lopez B, The CAT Study Group. Psychiatric comorbidity at the time of diagnosis in adults with ADHD: the CAT study. J Atten Disord. 2016;20(12):1066–75.

D’Agati E, Curatolo P, Mazzone L. Comorbidity between ADHD and anxiety disorders across the lifespan. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2019;23(4):238–44.

Goodman DW, Thase ME. Recognizing ADHD in adults with comorbid mood disorders: implications for identification and management. Postgrad Med. 2009;121(5):20–30.

Almeida MLG, Hernandez GAO, Ricardo-Garcell J. ADHD prevalence in adult outpatients with nonpsychotic psychiatric illnesses. J Atten Disord. 2007;11(2):150–6.

Nylander L, Holmqvist M, Gustafson L, Gillberg C. ADHD in adult psychiatry. Minimum rates and clinical presentation in general psychiatry outpatients. Nord J Psychiatry. 2009;63(1):64–71.

Deberdt W, Thome J, Lebrec J, Kraemer S, Fregenal I, Ramos-Quiroga JA, et al. Prevalence of ADHD in nonpsychotic adult psychiatric care (ADPSYC): a multinational cross-sectional study in Europe. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:242.

Fayyad J, De GR, Kessler R, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Demyttenaere K, et al. Cross-national prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:402–9.

Faraone SV, Spencer TJ, Montano CB, Biederman J. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: a survey of current practice in psychiatry and primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(11):1221–6.

Lebowitz MS. Stigmatization of ADHD: a developmental review. J Atten Disord. 2016;20(3):199–205.

Faraone SV, Asherson P, Banaschewski T, Biederman J, Buitelaar JK, Ramos-Quiroga JA, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15020.

Pawaskar M, Fridman M, Grebla R, Madhoo M. Comparison of quality of life, productivity, functioning and self-esteem in adults diagnosed with ADHD and with symptomatic ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2020;24(1):136–44.

Offord DR, Kraemer HC. Risk factors and prevention. Evid Based Ment Health. 2000;3(3):70–1.

Carpena MX, Munhoz TN, Xavier MO, Rohde LA, Santos IS, Del-Ponte B, et al. The role of sleep duration and sleep problems during childhood in the development of ADHD in adolescence: findings from a population-based birth cohort. J Atten Disord. 2020;24(4):590–600.

Liu CY, Asherson P, Viding E, Greven CU, Pingault JB. Early predictors of de novo and subthreshold late-onset ADHD in a child and adolescent cohort. J Atten Disord. 2021;25(9):1240–50.

Meinzer MC, Pettit JW, Viswesvaran C. The co-occurrence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and unipolar depression in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34(8):595–607.

Mowlem FD, Rosenqvist MA, Martin J, Lichtenstein P, Asherson P, Larsson H. Sex differences in predicting ADHD clinical diagnosis and pharmacological treatment. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;28(4):481–9.

So M, Dziuban EJ, Pedati CS, Holbrook JR, Claussen AH, O’Masta B et al. Childhood physical health and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of modifiable factors. Prev Sci. 2022.

Levy LD, Fleming JP, Klar D. Treatment of refractory obesity in severely obese adults following management of newly diagnosed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Int J Obes (Lond). 2009;33(3):326–34.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 45 CFR 46: pre-2018 requirements [Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/index.html#46.101.

Able SL, Johnston JA, Adler LA, Swindle RW. Functional and psychosocial impairment in adults with undiagnosed ADHD. Psychol Med. 2007;37(1):97–107.

Schein J, Adler LA, Childress A, Gagnon-Sanschagrin P, Davidson M, Kinkead F, et al. Economic burden of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adults in the United States: a societal perspective. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2022;28(2):168–79.

Palladino VS, McNeill R, Reif A, Kittel-Schneider S. Genetic risk factors and gene-environment interactions in adult and childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Genet. 2019;29(3):63–78.

Thapar A, Cooper M, Eyre O, Langley K. What have we learnt about the causes of ADHD? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54(1):3–16.

Straub L, Bateman BT, Hernandez-Diaz S, York C, Zhu Y, Suarez EA, et al. Validity of claims-based algorithms to identify neurodevelopmental disorders in children. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2021;30(12):1635–42.

Gruschow SM, Yerys BE, Power TJ, Durbin DR, Curry AE. Validation of the use of electronic health records for classification of ADHD status. J Atten Disord. 2019;23(13):1647–55.

Classi PM, Le TK, Ward S, Johnston J. Patient characteristics, comorbidities, and medication use for children with ADHD with and without a co-occurring reading disorder: a retrospective cohort study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2011;5:38.

Shi Y, Hunter Guevara LR, Dykhoff HJ, Sangaralingham LR, Phelan S, Zaccariello MJ, et al. Racial disparities in diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a US national birth cohort. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e210321.

Schein J, Childress A, Adams J, Gagnon-Sanschagrin P, Maitland J, Qu W, et al. Treatment patterns among children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the United States - A retrospective claims analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):555.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by Flora Chik, PhD, MWC, an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., and funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc.

Funding

Financial support for this research was provided by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. The study sponsor was involved in several aspects of the research, including the study design, the interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MC, MGL, RB, EA, and AG contributed to study conception and design, collection and assembly of data, and data analysis and interpretation. JS and AC contributed to study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation. All authors reviewed and approved the final content of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Data analyzed in this study are de-identified and comply with the patient requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA); therefore, no review by an institutional review board nor informed consent was required per Title 45 of CFR, Part 46.101(b)(4) [24].

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

JS is an employee of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. AC received research support from Allergan, Takeda/Shire, Emalex, Akili, Ironshore, Arbor, Aevi Genomic Medicine, Neos Therapeutics, Otsuka, Pfizer, Purdue, Rhodes, Sunovion, Tris, KemPharm, Supernus, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration; was on the advisory board of Takeda/Shire, Akili, Arbor, Cingulate, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Otsuka, Pfizer, Purdue, Adlon, Rhodes, Sunovion, Tris, Supernus, and Corium; received consulting fees from Arbor, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Purdue, Rhodes, Sunovion, Tris, KemPharm, Supernus, Corium, Jazz, Tulex Pharma, and Lumos Pharma; received speaker fees from Takeda/Shire, Arbor, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Pfizer, Tris, and Supernus; and received writing support from Takeda /Shire, Arbor, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Pfizer, Purdue, Rhodes, Sunovion, and Tris. MC, MGL, RB, EA, and AG are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc.

Previous presentation

Part of the material in this manuscript was presented at the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) 2023 conference held on May 7–10, 2023, in Boston, MA, as a poster presentation.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Schein, J., Cloutier, M., Gauthier-Loiselle, M. et al. Risk factors associated with newly diagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: a retrospective case-control study. BMC Psychiatry 23, 870 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05359-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05359-7