- Systematic Review

- Open access

- Published:

Examining the mental health services among people with mental disorders: a literature review

BMC Psychiatry volume 24, Article number: 568 (2024)

Abstract

Background

Mental disorders are a significant contributor to disease burden. However, there is a large treatment gap for common mental disorders worldwide. This systematic review summarizes the factors associated with mental health service use.

Methods

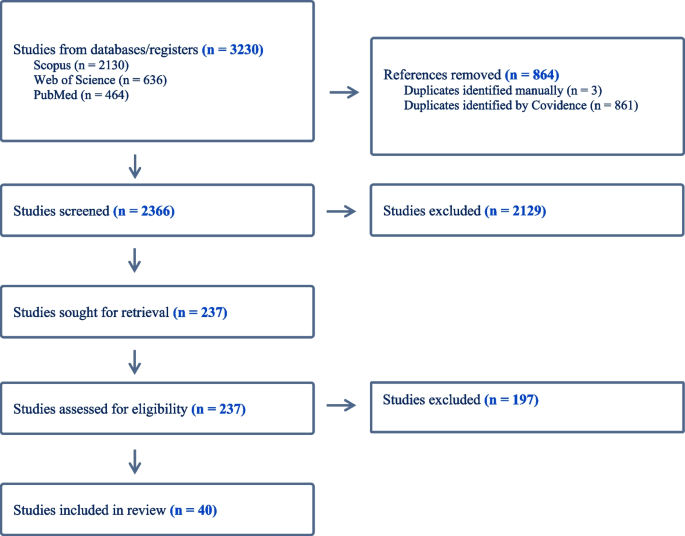

PubMed, Scopus, and the Web of Science were searched for articles describing the predictors of and barriers to mental health service use among people with mental disorders from January 2012 to August 2023. The initial search yielded 3230 articles, 2366 remained after removing duplicates, and 237 studies remained after the title and abstract screening. In total, 40 studies met the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Results

Middle-aged participants, females, Caucasian ethnicity, and higher household income were more likely to access mental health services. The use of services was also associated with the severity of mental symptoms. The association between employment, marital status, and mental health services was inconclusive due to limited studies. High financial costs, lack of transportation, and scarcity of mental health services were structural factors found to be associated with lower rates of mental health service use. Attitudinal barriers, mental health stigma, and cultural beliefs also contributed to the lower rates of mental health service use.

Conclusion

This systematic review found that several socio-demographic characteristics were strongly associated with using mental health services. Policymakers and those providing mental health services can use this information to better understand and respond to inequalities in mental health service use and improve access to mental health treatment.

Introduction

Mental disorders such as depression and anxiety are prevalent, with nationally representative studies showing that one-fifth of Australians experience a mental disorder each year [5]. More recent estimates derived from a similar survey during the period of the COVID-19 pandemic were 21.5% [11]. Mental illness can reduce the quality of life, and increase the likelihood of communicable and non-communicable diseases [116, 137], and is among the costliest burdens in developed countries [22, 34, 80]. The National Mental Health Commission [96] stated that the annual cost of mental ill-health in Australia was around $4000 per person or $60 billion. The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2019 reported that mental disorders rank the seventh leading cause of disability-adjusted life years and the second leading cause of years lived with disability [48]. Helliwell et al. [56] indicated that chronic mental illness was a key determinant of unhappiness, and it triggered more pain than physical illness. Mental health issues can have a spillover effect on all areas of life, poor mental health conditions might lead to lower educational achievements and work performance, substance abuse, and violence [102]. In Australia, despite considerable additional investment in the provision of mental health services research suggests that the rate of psychological distress at the population level has been increasing [38], this has been argued to reflect that people who most need mental health treatment are not accessing services. Insufficient numbers of mental health services and mental healthcare professionals and inadequate health literacy have been reported as the pivotal determinants of poor mental health [18]. Previous studies have reported large treatment gaps in mental health services; finding only 42–44% of individuals with mental illness seek help from any medical or professional service provider [85, 112] and this active proportion was much lower in low and middle-income countries [32, 114, 130].

Several studies have investigated factors associated with high and low rates of mental health service use and identified potential barriers to accessing mental health service use. Demographic, social, and structural factors have been associated with low rates of mental health service use. Structural barriers include the availability of mental health services and high treatment costs, social barriers to treatment access include stigma around mental health [125], fear of being perceived as weak or stigmatized [79], lack of awareness of mental disorders, and cultural stigma [17].

Existing studies that have systematically reviewed and evaluated the literature examining mental health service use have largely been constrained to specific population groups such as military service members [63] and immigrants [33], children and adolescents [35], young adults [76], and help-seeking among Filipinos in the Philippines [93]. These systematic reviews emphasize mental health service use by specific age groups or sub-groups, and the findings might not represent the patterns and barriers to mental health service use in the general population. One paper has reviewed mental health service use in the general adult population. Roberts et al. [112] found that need factors (e.g. health status, disability, duration of symptoms) were the strongest determinants of health service use for those with mental disorders.

The study results from Roberts et al. [112] were retrieved in 2016, and the current study seeks to build on this prior review with more recent research data by identifying publications since 2012 on mental health service use with a focus on high-income countries. This is in the context of ongoing community discussion and reform of the design and delivery of mental health services in Australia [140], and the need for current evidence to inform this discussion in Australia and other high-income countries. This systematic review aims to investigate factors associated with mental health service use among people with mental disorders and summarize the major barriers to mental health treatment. The specific objectives are (1) to identify factors associated with mental health service use among people with mental disorders in high-income countries, and (2) to identify commonly reported barriers to mental health service use.

Methodology

Selection procedures

Our review adhered to PRISMA guidelines to present the results. We utilized PubMed, Scopus, and the Web of Science to search for articles describing the facilitators and barriers to mental health service use among people with mental illness from January 2012 up to August 2023. There were no specific factors that were of interest as part of conducting this systematic review, instead, the review had a broad focus intending to identify factors shown to be associated with mental health service use in the recent literature. The keywords used in our search of electronic databases were related to mental disorders and mental health service use. The full search terms and strategies were shown in Supplementary Table 1. We uploaded the search results to Covidence for deduplication and screening. After eliminating duplicates, the first author retrieved the title abstract and full-text articles for all eligible papers. Then each title and abstract were screened by two independent reviewers, to select those that would progress to full-text review. Subsequently, the two reviewers screened the full text of all the selected papers and conducted the data extraction for those that met the eligibility criteria. There were discrepancies in 12% of the papers reviewed, and all conflicts were resolved through discussion and agreed on by at least three authors.

Selection criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In this systematic review, the scope was restricted to studies that draw samples from the general population, and the participants were either diagnosed with mental disorders or screened positive using a standardized scale. Case-control studies and cohort studies were considered for inclusion. The applied inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1.

Data extraction

After the full-text screening, details from all eligible studies were extracted by field into a data extraction table with thematic headings. The descriptive data includes the study title, author, publication year, geographic location, sample size, population details (gender, age), type of study design, mental disorder type (medical diagnosis or using scales) and quality grade (e.g. good, fair, and poor).

Quality assessment

The Newcastle Ottawa Scale [136] was used to evaluate the study quality for all eligible papers. We assessed the cross-sectional and cohort studies using separate assessment forms and graded each study as good, fair, or poor. The quality grade for each study was included in the data extraction table. The first author conducted the quality assessment using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale for cohort studies and the adapted scale for cross-sectional studies.

Results

The search process is summarized in Fig. 1. The initial search from PubMed, Scopus, and the Web of Science yielded 3230 articles: 2366 remained after removing duplicates; 2129 studies were considered not relevant; and 237 studies remained following title and abstract screening. In total, 40 studies met the inclusion criteria. Of these, four were cohort studies while thirty-six were cross-sectional studies. Ten studies (25.0%) were conducted in Canada, and nine (22.5%) were from the United States. Three studies used data from Germany (7.5%). Two studies each reported data from Australia, Denmark, Sweden, Singapore, or South Korea (5.0% of studies for each country). A single study was included with data from either the United Kingdom, Italy, Israel, Portugal, Switzerland, Chile, New Zealand, or reported pooled multinational data from six European countries (each country/ study representing 2.5% of the total sample of studies) (Table 2).

Study characteristics

As shown in Tables 2, 3 and 4, the sample size of studies varies; a cross-sectional study from Canada had the largest sample which contained over seven million participants [39], while the smallest sample size was 362 [100]. Sixteen studies (40.0%) used DSM-IV diagnoses [4] to measure mental disorders, twelve studies (30.0%) applied the International Classification of Disease [138], and six studies used (15.0%) the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale [69]. Only three studies (7.5%) had a hospital diagnosis of mental disorders, while three studies (7.5%) used the Patient Health Questionnaire [72] to define mental disorders.

Twenty-seven studies (67.5%) analyzed the rate of mental health service use over the last 12 months, six studies (15.0%) focused on lifetime service use, and three studies (7.5%) assessed both 12-month and lifetime mental health service use. A few studies examined other time frames, with single studies investigating mental health service use over the past 3 months, 5 years, and 7 years, and one included study considered mental health service use during the 24 months before and after a sibling’s death.

Twenty of the forty studies were classified as good quality (50.0%), seventeen as fair (42.5%), and three as poor quality (7.5%).

Overview of samples and factors investigated

The included studies examined a range of different factors associated with mental health service use. These included gender, age, marital status, ethnic groups, alcohol and drug abuse, education and income level, employment status, symptom severity, and residential location. The review identified service utilization factors related to socio-demographics, differences in utilization across countries, emerging socio-demographic factors and contexts, as well as structural and attitudinal barriers. These are described in further detail below.

Socio-demographic characteristics

Gender

Fifteen studies analyzed the association between gender and mental health service use, with fourteen studies reporting that mental health service use was more frequent among females with mental disorders than males [2, 37, 42, 43, 47, 54, 66, 67, 90, 103, 119, 123, 128, 130]. A South Korean study concluded that gender was not associated with mental health service use [100], which might be due to the small sample size of 362 participants in the study.

Age

Fourteen studies investigated age in association with mental health service use. Nine studies concluded that mental health service use was lower among young and old adult groups, with middle-aged persons with a mental disorder being most likely to access treatment from a mental health professional [26, 42, 43, 47, 54, 66, 67, 123, 130]. Forslund et al. [43] reported that mental health service use for women in Sweden peaked in the 45-to-64-year age group, while amongst males, mental health service use was stable across the lifespan. In contrast, two articles from New Zealand and Singapore each reported that young adults were the age group most likely to access services [28, 119]. Reich et al. [103] concluded that age was unrelated to mental health service use when considered for the whole population, but sex-specific analyses reported that mental health service use was higher in older than younger females, while the opposite pattern was observed for males. A Canadian study using community health survey data also observed no significant age-related differences in mental health service use [104].

Marital status

There was mixed evidence concerning marital status. Studies from the United States and Germany concluded that participants who were married or cohabiting had lower rates of mental health service use [26, 90], while Silvia et al. [120] found that mental health service use was higher among married participants in Portugal. Shafie et al. [119] reported being widowed was associated with lower rates of mental health service use in Singapore.

Ethnic groups

Eight studies examined the relationship between ethnic background and mental healthcare service use. Non-Hispanic White respondents were more likely to use mental health services in Canada and the United States [24, 26, 30, 130, 139], while Asians showed lower rates of mental health service use [28, 139]. Chow & Mulder [28] investigated mental health service use among Asians, Europeans, Maori, and Pacific peoples in New Zealand. They concluded that Maori had the highest rate of mental health service use compared with other ethnic groups. De Luca et al. [30] reported that mental health service use was lower among ethnic minority non-veterans compared to veterans in the United States, especially for those with Black or Hispanic backgrounds. In contrast, a study conducted in the UK found that mental health service use did not vary by ethnicity, with no difference between white and non-white persons [54].

Alcohol and drug abuse

Two studies reported risky alcohol use was negatively associated with mental health service use [26, 132]. However, within the time frame of the current review, there was insufficient published evidence on the impact of drug abuse on mental health service use among people with mental disorders. Choi, Diana & Nathan [26] found that drug abuse can lead to lower rates of mental health service use in the United States. In contrast, Werlen et al. [132] reported that risky use of (non-prescribed) prescription medications was associated with higher rates of mental health service use in Switzerland.

Education, income, and employment status

Four studies analyzed the relationship between education level, income, and mental health service use. Higher levels of educational attainment [26, 120] and higher income [26] were generally reported to be associated with an increased likelihood of mental health service use. However, Reich et al. [103] observed that in Germany, high education and perceived middle or high social class were associated with reduced mental health service use. One paper reported no significant difference in mental health service use in South Korea, possibly due to the small number of people accessing mental healthcare services [100].

Three studies reported that compared to those who are unemployed, those in work were less likely to use mental health services [26, 90, 119]. This outcome aligned with a Canadian study consisting of immigrants and general populations, Islam et al. [66] concluded that immigrants who were currently unemployed had higher odds of seeking treatment than those who were employed. However, an Italian [123] and a South Korean study [100] found that employment status was not related to mental health service use.

Symptom severity

Ten studies investigated the association between symptom severity and mental health service use and ten papers concluded that participants with moderate or serious psychological symptoms were more likely to use mental health services compared to those with mild symptoms [23, 27, 66, 103, 120, 123, 130, 139]. Other studies showed that study participants who viewed their mental health as poor [42], who were diagnosed with more than one mental disorder [103], and those who recognized their own need for mental health treatment [54, 139] were more likely to receive mental health services.

Residential location

Three studies investigated the association between residential location and mental health service use. Volkert et al. [128] concluded that the rates of mental health service use in Germany were significantly lower among those living in Canterbury than those living in Hamburg. A Canadian study found individuals living in neighborhoods where renters outnumber homeowners were less likely to access mental health services [42]. In the United States, for participants with low or moderate mental illness, mental health service use was lower for those residing closer to clinics [46].

Immigrants & refugees

The reviewed research found that non-refugee immigrants had slightly higher rates of mental health service use than refugees [10]. Other research found that long-term residents were more likely to access services than immigrants regardless of their origin [31, 134]. For example, Italian citizens were found to have higher rates of mental health service use compared to immigrants, especially for affective disorders [123]. In Canada, immigrants from West and Central Africa were more likely to access mental health services compared to immigrants from East Asia and the Pacific [31]. Research from Chile found that the rates of mental health service use were similar for immigrants and non-immigrants [40]. Although, a positive association between the severity of symptoms and rates of mental health service use was only observed among immigrants [40]. Whitley et al. [134] found that immigrants born in Asia or Africa had lower rates of mental health service use, but higher rates of service satisfaction scores compared to immigrants from other countries.

Emerging areas

Our literature review identified several areas in which only a small number of studies were found. We briefly describe them here as these may reflect emerging areas of research interest. Few published articles examined mental health treatment among participants with mental disorders together with chronic physical health conditions, and we only included the papers in this systematic review if they contained a healthy comparison group. We identified two papers that focused on survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer [68] and participants with physical health problems [110]. Both studies reported that participants with other chronic conditions reported higher rates of mental health service use than the general population [68, 110].

Two studies compared treatment seeking among people experiencing stressful life events. Erlangsen et al. [39] investigated the impact of spousal suicide, and Gazibara et al. [45] examined the effect of a sibling’s death on mental health service use. People bereaved by relatives’ deaths were more likely to use mental health services than the general population [39, 45]. The peak effect was observed in the first 3 months after the death for both genders, while evidence of an increase in mental health service use was evident up to 24 months before a sibling’s death and remained evident for at least 24 months after the death [45].

One paper studied the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown on mental health service use. An Israeli study concluded that compared to 2018 and 2019, adults reported they were reluctant to receive treatment during the pandemic lockdown and observed a decrease in mental health service use [13].

Structural and attitudinal barriers

In addition to the research considering a range of population characteristics (e.g. male, younger, or older age), several papers examined how attitudinal and structural factors were associated with mental health service use. The most frequently reported of these factors were cost [23, 46, 68, 120], lack of transportation [46, 83], inadequate services/ lack of availability [23, 46, 83, 128], poor understanding of mental disorders and what services were available [10, 11, 22, 83, 100, 105, 120], language difficulties [10], and stigma-related barriers [83, 100, 103, 105, 128]. Cultural issues and personal beliefs may influence the understanding of mental disorders and prevent people from using mental health services due to mistrust or fear of treatment [100, 128]. The review also observed some unique barriers to different population groups. Choi, Diana & Nathan [26] mentioned that lack of readiness and treatment cost were the biggest difficulties for older adults, while young participants were more concerned about stigma. Females also reported childcare as a factor limiting their ability to use mental health services, while the evidence reviewed argued that males prefer to solve mental health issues on their own, with internal control beliefs and lack of social support likely reducing their use of mental health services [37, 103].

Discussion

Summary of evidence

This systematic review investigated mental health service use among people with mental disorders and identified the factors associated with service use in high-income countries.

Most studies found that females with mental health conditions were more likely to use mental health services than males. The relationship between age and mental health service use was bell-shaped, with middle-aged participants having higher rates of mental health service use than other age groups. Possible explanations included that the elderly might be reluctant to disclose mental health symptoms, they might attribute their mental health symptoms to increasing age [20], and they may prefer to self-manage instead of seeking help from health professionals [44]. Caucasian ethnicity and higher household income were also associated with higher rates of mental health service use. Greater use of mental health services was observed in participants with severe mental symptoms, including among veterans [19, 37, 92]. Two studies also concluded that compared to other cultural groups, Asian respondents were more likely to receive treatment when problems were severe or had disabling effects [86, 97]. There was mixed evidence regarding employment status, although some studies found employment to be negatively related to receiving treatment [26, 90], and unemployed people are more likely to seek help [119]. There was inconsistent evidence for the association between marital status and service utilization. This contradictory evidence on marital status might be attributed to a lack of specification, some papers categorize it as married and non-married [26, 71, 131], while others further differentiate between those who were widowed, separated, and divorced [90, 119].

Immigrants

A number of studies showed that immigrants can face unique stressors owing to their experience of migration, which may exacerbate or be the source of their mental health issues, and impact the use of mental health services [1, 8]. These include separation from families, support networks, linguistic and cultural barriers [9, 113].

Due to the increased number of international migrants, immigrants’ mental health status and healthcare use has drawn growing attention [7, 77, 99]. Kirmayer et al. [70] and Helman [57] found that culture might be associated with people’s attitudes and understanding of mental health, influencing help-seeking behaviors. In general, the current results showed that immigrants and refugees were less likely to use mental health services than their native-born counterparts, and this finding was consistent with previous studies [75, 82, 127]. For immigrants, the length of stay in the host country was closely related to rates of mental health service use, which was argued to reflect increasing familiarity with the host culture and language proficiency [1, 59].

Emerging areas

Both mental disorders and chronic diseases contribute significantly to the global burden of disease. Prior studies have shown that people with chronic disease have a higher chance of experiencing psychological distress [6, 14, 68, 73], and vice versa [49, 74]. Hendrie et al. [58] concluded that respondents with chronic diseases were more likely to attend mental healthcare and reported higher costs. Negative experiences and stressful consequences related to chronic disease might contribute to the increased potential for mental illness but more opportunities to seek help from health professionals [60, 108, 135]. People with chronic diseases and mental health problems might experience more long-term pain and limitations in their daily lives, and these stressors can exacerbate their health conditions, and impact their attitude toward seeking help.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a major impact on mental health service use worldwide, the hospital admission and consultation rate decreased dramatically during the first pandemic year [118]. This reduction in service access might be a side effect of social distancing measures taken as mitigation measures, reducing both inciting incidents and physical access to services.

Financial difficulty, service availability, and stigma were frequently identified in the literature as structural and attitudinal factors associated with lower rates of mental health service use. These factors were associated with the different rates of mental health service use for different ethnicities. For example, Asian people were less likely than other groups to identify cost as a factor limiting their use of mental health services, with a major barrier for Asian people being stigma and cultural factors [139].

Limitations

This systematic review employed a broad search strategy with broad search terms to capture relevant articles. Rather than emphasizing a particular mental disorder, this review focused on the rates of mental health service use among adults aged 18 years or older who were experiencing a common mental disorder. However, this review still contained limitations. First was the potential for selection bias. Although we used various search terms for mental health service use and mental disorder, it is possible that the service use was not the primary research question for some papers, or that the relevant service use outcome was not statistically significant- in these cases, if the information was not reported in the abstract, relevant papers might have been missed. It is also important to note that this systematic review includes studies conducted in different countries and that the mental health systems and opportunities for access vary among countries. We only searched for full-text peer-reviewed articles published in English. Grey literature and papers published in other languages were excluded from the search. Most of the included literature used self-reported data to measure service access, and these data can be liable to recall bias. Studies using administrative data were also included in the systematic review, and we note that although they have large datasets, compared to survey data, there is often a lack of adequate control variables included to minimize possible confounding influences.

Future research

There is a need for more published articles on several aspects that may influence the service utilization among people with mental disorders, including the impact of residential or neighborhood areas, and household income across various income groups. These aspects are important population characteristics that require further research to inform the targeting and type of support (e.g. low-cost, accessible). Additionally, there was a lack of longitudinal research on mental health service use, future studies could use the data to identify changes over time and relate events to specific exposures (e.g. Covid-19 pandemic). Future studies can investigate the cost of mental health treatment in detailed aspects, (e.g. publicly funded mental health services, community-based support for free or low-cost mental health services). Overall, there was a lack of studies for ethnic minorities, given ethnic minority groups were more vulnerable to mental disorders but with less mental health service use. Future research can expand gender identity representation in data collection and move beyond the binary genders. People with non-binary gender identities can face greater challenges and disadvantages in mental health and mental health service use.

Conclusion

This review identified that middle-aged, female gender, Caucasian ethnicity, and severity of mental disorder symptoms were factors consistently associated with higher rates of mental health service use among people with a mental disorder. In comparison, the influence of employment and marital status on mental health service use was unclear due to the limited number of published studies and/ or mixed results. Financial difficulty, stigma, lack of transportation, and inadequate mental health services were the structural barriers most consistently identified as being associated with lower rates of mental health service use. Finally, ethnicity and immigrant status were also associated with differences in understanding of mental health (i.e. mental health literacy), effectiveness of mental health treatments, as well as language difficulties. The insights gained through this review on the factors associated with mental health service use can help clinicians and policymakers to identify and provide more targeted support for those least likely to access services, and this in turn may contribute to reducing inequalities in not only mental health service use but also the burden of mental disorders.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials related to the study are available on request from the first author, yunqi.gao@anu.edu.au.

References

Abe-Kim J, Takeuchi DT, Hong S, Zane N, Sue S, Spencer MS, et al. Use of mental health–related services among immigrant and US-born Asian americans: results from the national latino and Asian American study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):91–8.

Abramovich A, De Oliveira C, Kiran T, Iwajomo T, Ross LE, Kurdyak P. Assessment of health conditions and health service use among transgender patients in Canada. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2015036. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.15036.

Ambikile JS, Iseselo MK. Mental health care and delivery system at Temeke hospital in Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1271-9.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2017-18, Mental health, ABS, viewed 23 July 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/mental-health/2017-18.

Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(6):1069–78.

Bacon L, Bourne R, Oakley C, Humphreys M. Immigration policy: implications for mental health services. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2010;16:124–32.

Bhatia S, Ram A. Theorizing identity in transnational and diaspora cultures: a critical approach to acculturation. Int J Intercultural Relations. 2009;33:140–9.

Bhugra D. Migration, distress and cultural identity. Br Med Bull. 2004;69:129–41.

Björkenstam E, Helgesson M, Norredam M, Sijbrandij M, de Montgomery CJ, Mittendorfer-Rutz E. Differences in psychiatric care utilization between refugees, non-refugee migrants and Swedish-born youth. Psychol Med. 2022;52(7):1365–75. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291720003190.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2020–2022). National study of mental health and wellbeing. ABS. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-study-mental-health-and-wellbeing/latest-release.

Blais RK, Tsai J, Southwick SM, Pietrzak RH. Barriers and facilitators related to mental health care use among older veterans in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(5):500–6. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300469.

Blasbalg U, Sinai D, Arnon S, Hermon Y, Toren P. Mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic: results from a large-scale population-based study in Israel. Compr Psychiatr. 2023;123:123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2023.152383.

Bodurka-Bevers D, Basen-Engquist K, Carmack CL, Fitzgerald MA, Wolf JK, Moor Cd, Gershenson DM. Depression, anxiety, and quality of life in patients with epthelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;78:302–8.

Bondesson E, Alpar T, Petersson IF, Schelin MEC, Jöud A. Health care utilization among individuals who die by suicide as compared to the general population: a population-based register study in Sweden. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1616. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14006-x

Borges G, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Andrade L, Benjet C, Cia A, Kessler RC, Orozco R, Sampson N, Stagnaro JC, Torres Y, Viana MC, Medina-Mora ME. Twelve-month mental health service use in six countries of the Americas: a regional report from the World Mental Health Surveys. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;29:e53. https://doi.org/10.1017/s2045796019000477.

Brenman NF, Luitel NP, Mall S, Jordans MJD. Demand and access to mental health services: a qualitative formative study in Nepal. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2014;14(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-698X-14-22. PMID: 25084826.

Budhathoki SS, Pokharel PK, Good S, Limbu S, Bhattachan M, Osborne RH. The potential of health literacy to address the health related UN sustainable development goal 3 (SDG3) in Nepal: a rapid review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1943-z. PMID: 28049468.

Brown JS, Evans-Lacko S, Aschan L, Henderson MJ, Hatch SL, Hotopf M. Seeking informal and formal help for mental health problems in the community: a secondary analysis from a psychiatric morbidity survey in South London. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):275.

Burroughs H, Lovell K, Morley M, Baldwin R, Burns A, Chew-Graham C. Justifiable depression’: how primary care professionals and patients view late-life depression? A qualitative study. Fam Pract. 2006;23(3):369–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmi115.

Caron J, Fleury MJ, Perreault M, Crocker A, Tremblay J, Tousignant M, Kestens Y, Cargo M, Daniel M. Prevalence of psychological distress and mental disorders, and use of mental health services in the epidemiological catchment area of Montreal South-West. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-183.

Chan CMH, Ng SL, In S, Wee LH, Siau CS. Predictors of psychological distress and mental health resource utilization among employees in Malaysia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010314.

Chaudhry MM, Banta JE, McCleary K, Mataya R, Banta JM. Psychological distress, structural barriers, and health services utilization among U.S. adults: National Health interview survey, 2011–2017. Int J Mental Health. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207411.2022.2123694

Chiu M, Amartey A, Wang X, Kurdyak P, Luppa M, Giersdorf J, Riedel-Heller S, Prütz F, Rommel A. Ethnic differences in mental health status and service utilization: a population-based study in Ontario, Canada frequent attenders in the German healthcare system: determinants of high utilization of primary care services. Results from the cross-sectional. Can J PsychiatryBMC Fam Pract. 2018;6321(71):481–91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-020-1082-9.

Cho SJ, Lee JY, Hong JP, Lee HB, Cho MJ, Hahm BJ. Mental health service use in a nationwide sample of Korean adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44:943–51.

Choi NG, DiNitto DM, Marti CN. Treatment use, perceived need, and barriers to seeking treatment for substance abuse and mental health problems among older adults compared to younger adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;145:113–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.004.

Chong SA, Abdin E, Vaingankar JA, Kwok KW, Subramaniam M. Where do people with mental disorders in Singapore go to for help? Ann Acad Med Singap. 2012;41(4):154–60.

Chow CS, Mulder RT. Mental health service use by asians: a New Zealand census. N Z Med J. 2017;130(1461):35–41.

Dang HM, Lam TT, Dao A, Weiss B. Mental health literacy at the public health level in low and middle income countries: an exploratory mixed methods study in Vietnam. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(12):e0244573. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244573

De Luca SM, Blosnich JR, Hentschel EA, King E, Amen S. Mental health care utilization: how race, ethnicity and veteran status are associated with seeking help. Community Ment Health J. 2016;52(2):174–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-015-9964-3.

Durbin A, Moineddin R, Lin E, Steele LS, Glazier RH. Mental health service use by recent immigrants from different world regions and by non-immigrants in Ontario, Canada: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):336. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0995-9

Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine J, et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. JAMA. 2004;291(21):2581–90.

Derr AS. Mental health service use among immigrants in the United States: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67:265–74. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500004.

Dimoff JK, Kelloway EK. With a little help from my Boss: the impact of workplace mental health training on leader behaviors and employee resource utilization. J Occup Health Psychol. 2019;24:4–19.

Duong MT, Bruns EJ, Lee K, et al. Rates of mental health service utilization by children and adolescents in schools and other common service settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2021;48:420–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-020-01080-9.

Edman JL, Kameoka VA. Cultural differences in illness schemas: an analysis of Filipino and American illness attributions. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1997;28(3):252–65.

Elbogen EB, Wagner HR, Johnson SC, Kinneer P, Kang H, Vasterling JJ, Timko C, Beckham JC. Are Iraq and Afghanistan veterans using mental health services? New data from a national random-sample survey. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(2):134–41. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.004792011.

Enticott J, Dawadi S, Shawyer F, Inder B, Fossey E, Teede H, Rosenberg S, Ozols Am I, Meadows G. Mental Health in Australia: psychological distress reported in six consecutive cross-sectional national surveys from 2001 to 2018. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:815904. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.815904

Erlangsen A, Runeson B, Bolton JM, Wilcox HC, Forman JL, Krogh J, Katherine Shear M, Nordentoft M, Conwell Y. Association between spousal suicide and mental, physical, and social health outcomes a longitudinal and nationwide register-based study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):456–64. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0226.

Errazuriz A, Schmidt K, Valenzuela P, Pino R, Jones PB. Common mental disorders in Peruvian immigrant in Chile: a comparison with the host population. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1274. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15793-7

Evans-Lacko S, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, Alonso J, Benjet C, Bruffaerts R, Chiu WT, Florescu S, de Girolamo G, Gureje O, Haro JM, He Y, Hu C, Karam EG, Kawakami N, Lee S, Lund C, Kovess-Masfety V, Levinson D, Thornicroft G. Socio-economic variations in the mental health treatment gap for people with anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Psychol Med. 2018;48(9):1560–71. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291717003336.

Fleury MJ, Grenier G, Bamvita JM, Perreault M, Kestens Y, Caron J. Comprehensive determinants of health service utilisation for mental health reasons in a Canadian catchment area. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11(1):20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-11-20

Forslund T, Kosidou K, Wicks S, Dalman C. Trends in psychiatric diagnoses, medications and psychological therapies in a large Swedish region: a population-based study. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):328. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02749-z

Garrido MM, Kane RL, Kaas M, Kane RA. Use of mental health care by community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(1):50–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03220.x.

Gazibara T, Ornstein KA, Gillezeau C, Aldridge M, Groenvold M, Nordentoft M, Thygesen LC. Bereavement among adult siblings: an examination of health services utilization and mental health outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2021;190(12):2571–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwab212.

Glasheen C, Forman-Hoffman VL, Hedden S, Ridenour TA, Wang J, Porter JD. Residential transience among adults: prevalence, characteristics, and association with mental illness and mental health service use. Community Ment Health J. 2019;55(5):784–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-019-00385-w.

Gonçalves DC, Coelho CM, Byrne GJ. The use of healthcare services for mental health problems by middle-aged and older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;59(2):393–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2014.04.013.

GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9:137–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3.

Goff DC, Sullivan LM, McEvoy JP, et al. A comparison of ten-year cardiac risk estimates in schizophrenia patients from the CATIE Study and matched controls. Schizophr Res. 2005;80(1):45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2005.08.010.

Goncalves Daniela C. From loving grandma to working with older adults: promoting positive attitudes towards aging. Educ Gerontol. 2009;35(3):202–25.

Gong F, Gage S-JL, Tacata LA Jr. Helpseeking behavior among Filipino americans: a cultural analysis of face and language. J Community Psychol. 2003;31:469–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.10063.

Grossbard JR, Lehavot K, Hoerster KD, Jakupcak M, Seal KH, Simpson TL. Relationships among veteran status, gender, and key health indicators in a national young adult sample. Psychiatric Serv. 2013;64(6):547–53. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.003002012.

Hajebi A, Motevalian SA, Rahimi-Movaghar A, Sharifi V, Amin-Esmaeili M, Radgoodarzi R, Hefazi M. Major anxiety disorders in Iran: prevalence, sociodemographic correlates and service utilization. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):261. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1828-2

Harber-Aschan L, Hotopf M, Brown JSL, Henderson M, Hatch SL. Longitudinal patterns of mental health service utilisation by those with mental-physical comorbidity in the community. J Psychosom Res. 2019;117:10–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.11.005.

Huýnh C, Caron J, Fleury MJ. Mental health services use among adults with or without mental disorders: do development stages matter? Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2016;62(5):434–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764016641906.

Helliwell JF, Layard R, Sachs JD, De Neve JE, Aknin LB, Wang S, editors. World Happiness Report 2022. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network; 2022.

Helman C. Culture, health and illness. 5th ed. CRC Press; 2007. https://doi.org/10.1201/b13281.

Hendrie HC, Lindgren D, Hay DP, et al. Comorbidity profile and healthcare utilization in elderly patients with serious mental illnesses. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(12):1267–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.056.

Hermannsdóttir BS, Aegisdottir S. Spirituality, connectedness, and beliefs about psychological services among Filipino immigrants in Iceland. Counsel Psychol. 2016;44(4):546–72.

Hoffman KE, McCarthy EP, Recklitis CJ, Ng AK. Psychological distress in long-term survivors of adult-onset cancer: results from a national survey. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1274–81.

Hoge C, Castro C, Messer S, McGurk D, Cotting D, Koffman R. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:13–22.

Hoge C, Grossman S, Auchterlonie J, Riviere L, Milliken C, Wilk J. PTSD treatment for soldiers after combat deployment: low utilization of mental health care and reasons for dropout. Psychiatric Serv. 2014;65(8):997–1004. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300307.

Hom MA, Stanley IH, Schneider ME, Joiner TE. A systematic review of help-seeking and mental health service utilization among military service members. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;53:59–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.01.008.

Hwang W, Miranda J, Chung C. Psychosis and shamanism in a Filipino–American immigrant. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2007;31(2):251–69.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. (Eds.). Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington National Academies Press (US). 2023. https://doi.org/10.17226/12875.

Islam F, Khanlou N, Macpherson A, Tamim H. Mental health consultation among Ontario’s immigrant populations. Community Ment Health J. 2018;54(5):579–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-017-0210-z.

Jacobi F, Groß J. Prevalence of mental disorders, health-related quality of life, and service utilization across the adult life span. Psychiatrie. 2014;11(4):227–33. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1670774.

Kaul S, Avila JC, Mutambudzi M, Russell H, Kirchhoff AC, Schwartz CL. Mental distress and health care use among survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer: a cross-sectional analysis of the National Health Interview Survey. Cancer. 2017;123(5):869–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30417.

Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–9.

Kirmayer LJ, Weinfeld M, Burgos G, et al. Use of health care services for psychological distress by immigrants in an urban multicultural milieu. Can J Psychiatry. 2007;52:295–304.

Kose T. Gender, income and mental health: the Turkish case. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0232344. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232344

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

Kugaya A, Akechi T, Okuyama T, Nakano T, Mikami I, Okamura H, Uchitomi Y. Prevalence, predictive factors, and screening for psychological distress in patients with newly diagnosed head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2000;88:2817–23.

Kurdyak PA, Gnam WH, Goering P, Chong A, Alter DA. The relationship between depressive symptoms, health service consumption, and prognosis after acute myocardial infarction: a prospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8: 200. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-8-200.

Le Meyer O, Zane N, Cho YI, Takeuchi DT. Use of specialty mental health services by Asian americans with psychiatric disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(5):1000–5. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017065.

Li W, Dorstyn DS, Denson LA. Predictors of mental health service use by young adults: a systematic review. Psychiatric Serv. 2016;67(9):946–56. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500280.

Lindert J, Schouler-Ocak M, Heinz A, Priebe S. Mental health, health care utilisation of migrants in Europe. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23 Suppl 1:14–20.

Lovering S. Cultural attitudes and beliefs about pain. J Transcult Nurs. 2006;17(4):389–95.

Luitel NP, Jordans MJD, Kohrt BA, Rathod SD, Komproe IH. Treatment gap and barriers for mental health care: A cross-sectional community survey in Nepal. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183223. PMID: 28817734.

Jansson I, Gunnarsson AB. Employers’ views of the impact of Mental Health problems on the ability to work. Work. 2018;59:585–98.

Kayiteshonga Y, Sezibera V, Mugabo L, Iyamuremye JD. Prevalence of mental disorders, associated co-morbidities, health care knowledge and service utilization in Rwanda - towards a blueprint for promoting mental health care services in low- and middle-income countries? BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1858. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14165-x.

Kirmayer LJ, Narasiah L, Munoz M, Rashid M, Ryder AG, Guzder J, Hassan G, Rousseau C, Pottie K, Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health (CCIRH). Common mental health problems in immigrants and refugees: general approach in primary care. Can Med Assoc J. 2011;183(12):E959-67. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.090292.

Kline AC, Panza KE, Nichter B, Tsai J, Harpaz-Rotem I, Norman SB, Pietrzak RH. Mental health care use among U.S. Military veterans: results from the 2019–2020 national health and resilience in veterans study. Psychiatr Serv. 2022;73(6):628–35. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202100112.

Knipscheer JW, Kleber RJ. Help-seeking behavior of west African migrants. J Community Psychol. 2008;36:915–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20264.

Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, Saraceno B. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(11):858–66.

Kung WW. Cultural and practical barriers to seeking mental health treatment for Chinese americans. J Community Psychol. 2004;32(1):27–43.

Lipson SK, Lattie EG, Eisenberg D. Increased rates of mental health service utilization by U.S. College students: 10-year population-level trends (2007–2017). Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(1):60–3. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800332.

Liu L, Chen XL, Ni CP, Yang P, Huang YQ, Liu ZR, Wang B, Yan YP. Survey on the use of mental health services and help-seeking behaviors in a community population in Northwestern China. Psychiatry Res. 2018;262:135–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.02.010.

Lu J, Xu X, Huang Y, Li T, Ma C, Xu G, Yin H, Ma Y, Wang L, Huang Z, Yan Y, Wang B, Xiao S, Zhou L, Li L, Zhang Y, Chen H, Zhang T, Yan J, Zhang N. Prevalence of depressive disorders and treatment in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(11):981–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00251-0.

Mack S, Jacobi F, Gerschler A, Strehle J, Höfler M, Busch MA, Maske UE, Hapke U, Seiffert I, Gaebel W, Zielasek J, Maier W, Wittchen HU. Self-reported utilization of mental health services in the adult German population–evidence for unmet needs? Results of the DEGS1-Mental Health Module (DEGS1-MH). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2014;23(3):289–303. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1438.

Mahar AL, Aiken AB, Cramm H, Whitehead M, Groome P, Kurdyak P. Mental health services use trends in Canadian veterans: a Population-based Retrospective Cohort Study in Ontario. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63(6):378–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743717730826.

Maneze D, DiGiacomo M, Salamonson Y, Descallar J, Davidson PM. Facilitators and barriers to health-seeking behaviours among Filipino migrants: inductive analysis to inform health promotion. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:506269.

Martinez AB, Co M, Lau J, et al. Filipino help-seeking for mental health problems and associated barriers and facilitators: a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020;55:1397–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01937-2.

McKibben JBA, Fullerton CS, Gray CL, Kessler RC, Stein MB, Ursano RJ. Mental health service utilization in the U.S. Army Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(4):347–53. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.000602012.

Mosier KE, Vasiliadis H-M, Lepnurm M, Puchala C, Pekrul C, Tempier R. Prevalence of mental disorders and service utilization in seniors: results from the Canadian community health survey cycle 1.2. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(10):960–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2434.

National Mental Health Commission. Economics of Mental Health in Australia. 2016. Available at: https://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/news-and-media/media-releases/2016/december/economics-of-mental-health-in-australia. Accessed: 20 July 2023.

Nicdao EG, Duldulao AA, Takeuchi DT. Psychological Distress, Nativity, and Help-Seeking among Filipino Americans. Education, Social Factors, and Health Beliefs in Health and Health Care Services. Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. 2015:107–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0275-495920150000033005.

Nock MK, Stein MB, Heeringa SG, Ursano RJ, Colpe LJ, Fullerton CS, et al. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal behavior among soldiers: results from the Army study to assess risk and resilience in service members (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):514–22. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.

Ortega AN, Fang H, Perez VH, Rizzo JA, Carter-Pokras O, Wallace SP, et al. Health care access, use of services, and experiences among undocumented mexicans and other latinos. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(21):2354–60.

Park S, Cho MJ, Bae JN, Chang SM, Jeon HJ, Hahm BJ, Son JW, Kim SG, Bae A, Hong JP. Comparison of treated and untreated major depressive disorder in a nationwide sample of Korean adults. Community Ment Health J. 2012;48(3):363–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-011-9434-5.

Patel V, Saxena S, Lund C, et al. The lancet commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet. 2018;392:1553–98.

Patel V, Flisher AJ, Hetrick S, McGorry P. Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge. Lancet. 2007;369(9569):1302–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7.

Reich H, Niermann HCM, Voss C, Venz J, Pieper L, Beesdo-Baum K. Sociodemographic, psychological, and clinical characteristics associated with health service (non-)use for mental disorders in adolescents and young adults from the general population. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-023-02146-3.

Pelletier L, O’Donnell S, McRae L, Grenier J. The burden of generalized anxiety disorder in Canada. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2017;37(2):54–62. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.37.2.04.

Rim SJ, Hahm BJ, Seong SJ, Park JE, Chang SM, Kim BS, An H, Jeon HJ, Hong JP, Park S. Prevalence of Mental disorders and Associated factors in Korean adults: national mental health survey of Korea 2021. Psychiatry Invest. 2023;20(3):262–72. https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2022.0307.

Pols H, Oak S. War & military mental health: the US psychiatric response in the 20th century. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:2132–42.

Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S, Maj M, Maselko J, Phillips MR, Rahman A. No health without mental health. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):859–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61238-0.

Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff. 2013;32:1143–52.

Raphael MJ, Gupta S, Wei X, Peng Y, Soares CN, Bedard PL, Siemens DR, Robinson AG, Booth CM. Long-term mental health service utilization among survivors of testicular cancer: a population-based cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(7):779–86. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.20.02298.

Reaume SV, Luther AWM, Ferro MA. Physical morbidity and mental health care among young people. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68(3):540–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.040.

Reavley NJ, Morgan AJ, Petrie D, Jorm AF. Does mental health-related discrimination predict health service use 2 years later? Findings from an Australian national survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020;55(2):197–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01762-2.

Roberts T, Miguel Esponda G, Krupchanka D, Shidhaye R, Patel V, Rathod S. Factors associated with health service utilisation for common mental disorders: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):262. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1837-1.

Rogler LH. International migrations. A framework for directing research. Am Psychol. 1994;49(8):701–8.

Sagar R, Pattanayak RD, Chandrasekaran R, Chaudhury PK, Deswal BS, Singh RL, et al. Twelve-month prevalence and treatment gap for common mental disorders: findings from a large-scale epidemiological survey in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59(1):46.

Saxena S, Sharan P, Saraceno B. Budget and financing of mental health services: baseline information on 89 countries from WHO’s project atlas. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2003;6(3):135–43.

Sawyer MG, Whaites L, Rey JM, Hazell PL, Graetz BW, Baghurst P. Health-related quality of life of children and adolescents with mental disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(5):530–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200205000-00010.

Seal KH, Metzler TJ, Gima KS, Bertenthal D, Gaguen S, Marmar CR. Trends and risk factors for mental health diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans using department of veterans affairs health care, 2002–2008. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(9):1651–8.

Sepúlveda-Loyola W, Rodríguez-S´anchez I, P´erez-Rodríguez P, Ganz F, Torralba R, Oliveira DV, et al. Impact of social isolation due to COVID-19 on health in older people: mental and physical effects and recommendations. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;24(9):938–47.

Shafie S, Subramaniam M, Abdin E, Vaingankar JA, Sambasivam R, Zhang Y, Shahwan S, Chang S, Jeyagurunathan A, Chong SA. Help-seeking patterns among the general population in singapore: results from the Singapore mental health study 2016. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2021;48(4):586–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-020-01092-5.

Silva M, Antunes A, Azeredo-Lopes S, Cardoso G, Xavier M, Saraceno B, Caldas-de-Almeida JM. Barriers to mental health services utilisation in Portugal–results from the National mental health survey. J Mental Health. 2022;31(4):453–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2020.1739249.

Stecker T, Fortney J, Hamilton F, Ajzen I. An assessment of beliefs about mental health care among veterans who served in Iraq. Psychiatric Serv. 2007;58:1358–61.

Sodhi-Berry N, Preen DB, Alan J, Knuiman M, Morgan VA, Corrao G, Monzio Compagnoni M, Valsassina V, Lora A. Pre-sentence mental health service use by adult offenders in Western Australia: baseline results from a longitudinal whole-population cohort studyAssessing the physical healthcare gap among patients with severe mental illness: large real-world investigati. Crim Behav Ment HealthBJPsych Open. 2014;247(35):204–21. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.998.

Spinogatti F, Civenti G, Conti V, Lora A, Bahji A. Ethnic differences in the utilization of mental health services in Lombardy (Italy): an epidemiological analysisIncidence and correlates of opioid-related psychiatric emergency care: a retrospective, multiyear cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol J Opioid Manage. 2015;5016(13):59223–65226. https://doi.org/10.5055/jom.2020.0572.

The World Bank. Population, total, population, total - low income, middle income, high income. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank (producer and distributor); 2022. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?end=2022&locations=XM-XP-XD&start=1960&view=chart

Thornicroft G. Stigma and discrimination limit access to mental health care. Epidemiol Psychiatric Sci. 2008;17(1):14–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1121189X00002621.

Thornicroft G, Tansella M. Components of a modern mental health service: a pragmatic balance of community and hospital care: overview of systematic evidence. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:283–90.

Tiwari SK, Wang J. Ethnic differences in mental health service use among White, Chinese, south Asian and South East Asian populations living in Canada. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43(11):866–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0373-6.

Volkert J, Andreas S, Härter M, Dehoust MC, Sehner S, Suling A, Ausín B, Canuto A, Crawford MJ, Ronch D, Grassi C, Hershkovitz L, Muñoz Y, Quirk M, Rotenstein A, Santos-Olmo O, Shalev AB, Strehle AY, Weber J, Schulz K. Predisposing, enabling, and need factors of service utilization in the elderly with mental health problems. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(7):1027–37. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610217002526.

Wang N, Xie X. Associations of health insurance coverage, mental health problems, and drug use with mental health service use in US adults: an analysis of 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Aging Ment Health. 2019;23(4):439–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1441262.

Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):841–50.

Wei Z, Hu C, Wei X, Yang H, Shu M, Liu T. Service utilization for mental problems in a metropolitan migrant population in China. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(7):645–52. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201200304.

Werlen L, Puhan MA, Landolt MA, Mohler-Kuo M. Mind the treatment gap: the prevalence of common mental disorder symptoms, risky substance use and service utilization among young Swiss adults. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1470. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09577-6.

Wettstein A, Tlali M, Joska JA, Cornell M, Skrivankova VW, Seedat S, Mouton JP, van den Heuvel LL, Maxwell N, Davies MA, Maartens G, Egger M, Haas AD. The effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on mental health care use in South Africa: an interrupted time-series analysis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2022;31:e43. https://doi.org/10.1017/s2045796022000270.

Whitley R, Wang J, Fleury MJ, Liu A, Caron J. Mental health status, health care utilisation, and service satisfaction among immigrants in montreal: an epidemiological comparison. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(8):570–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743716677724.

Warner EL, Kent EE, Trevino KM, Parsons HM, Zebrack BJ, Kirchhoff AC. Social well-being among adolescents and young adults with cancer: a systematic review. Cancer. 2016;122:1029–37.

Wells G, Shea B, O’connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Department of Epidemiology and Community Medicine, University of Ottawa, Canada. Canada: University of Ottawa; 2000. Available at: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.Asp

Westerhof GJ, Keyes CL. Mental illness and mental health: the two continua model across the lifespan. J Adult Dev. 2010;17(2):110–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-009-9082-y.

World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992.

Yang KG, Rodgers CRR, Lee E, B LC. Disparities in mental health care utilization and perceived need among Asian americans: 2012–2016. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(1):21–7. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900126.

Rosenberg S, Hickie AMI. Making better choices about mental health investment: the case for urgent reform of Australia’s better access program. Australian New Z J Psychiatry. 2019;53(11):1052–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867419865335.

World Bank. World Bank income groups [dataset]. World Bank, Income Classifications [original data]. 2023. Retrieved May 2, 2024 from https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/world-bank-income-groups.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YG was responsible for the study design, title and abstract screening, full-text screening, and writing the manuscript. PB, RB, and LL contributed to the study design, title and abstract screening, full-text screening, and offered comments and detailed feedback on the draft paper. MC also helped with the title and abstract screening, full-text screening, and provided comments and detailed feedback on the draft paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, Y., Burns, R., Leach, L. et al. Examining the mental health services among people with mental disorders: a literature review. BMC Psychiatry 24, 568 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05965-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05965-z