- Research

- Open access

- Published:

Deprescribing psychotropic medicines for behaviours that challenge in people with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review

BMC Psychiatry volume 23, Article number: 202 (2023)

Abstract

Background

Clear evidence of overprescribing of psychotropic medicines to manage behaviours that challenges in people with intellectual disabilities has led to national programmes within the U.K. such as NHS England’s STOMP to address this. The focus of the intervention in our review was deprescribing of psychotropic medicines in children and adults with intellectual disabilities. Mental health symptomatology and quality of life were main outcomes.

Methods

We reviewed the evidence using databases Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, CINAHL and Open Grey with an initial cut-off date of 22nd August 2020 and an update on 14th March 2022. The first reviewer (DA) extracted data using a bespoke form and appraised study quality using CASP and Murad tools. The second reviewer (CS) independently assessed a random 20% of papers.

Results

Database searching identified 8675 records with 54 studies included in the final analysis.

The narrative synthesis suggests that psychotropic medicines can sometimes be deprescribed. Positive and negative consequences were reported. Positive effects on behaviour, mental and physical health were associated with an interdisciplinary model.

Conclusions

This is the first systematic review of the effects of deprescribing psychotropic medicines in people with intellectual disabilities which is not limited to antipsychotics. Main risks of bias were underpowered studies, poor recruitment processes, not accounting for other concurrent interventions and short follow up periods. Further research is needed to understand how to address the negative effects of deprescribing interventions.

Trial registration

The protocol was registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42019158079)

Background

Intellectual disabilities are a group of diverse developmental conditions characterised by lower intellectual functioning (usually an IQ of less than 70), and significant impairments of social or adaptive functioning, with an associated onset during childhood [1]. It is relatively common for people with intellectual disabilities to develop behaviours that challenge, with a prevalence of around 10–18% in individuals accessing educational, health or social care services [2,3,4]. Behaviours that challenge - defined as culturally abnormal behaviour, placing a person at risk of harm to themselves and others - can significantly affect engagement with community amenities due to their duration, intensity, or frequency [5]. These behaviours can include aggression, self-harm, withdrawal, and disruptive or destructive behaviour, including behaviours which may bring the person into contact with the criminal justice system [6].

Prescribing psychotropic medications to treat mental illness may be clinically appropriate for individuals with intellectual disabilities [7, 8]. However, no psychotropic medicines have marketing authorisations for behaviours that challenge in the absence of mental health conditions, except for the short-term use of risperidone and haloperidol for behavioural and psychological effects of dementia. Despite this, behaviours that challenge are independently associated with increased use of psychotropic medication [4, 9]. Psychotropics, particularly if used over a long period of time without adequate review and monitoring, can cause significant harm including: anticholinergic burden, tardive dyskinesia [10, 11], weight gain, and development of metabolic syndrome increasing morbidity and mortality [12]. Therefore, reducing the use of psychotropic medicines for individuals with intellectual disabilities and behaviours that challenge is indicated for reasons of health and quality of life, in addition to being a current policy priority [13, 14].

The purpose of the present paper is to report findings from a systematic review addressing the following question: What are the effects of deprescribing psychotropic medicines as a part of a care pathway or treatment plan for people of all ages with intellectual disabilities and behaviours that challenge? A previous systematic review of deprescribing psychotropic medicines in adults with intellectual disabilities was restricted to antipsychotic medicines involving databases searched between 1st January 1990 and 1st March 2016 [15]. Our review extends this evidence base by including all psychotropic medicines used with children or adults and including research since 2016.

Methods

The review was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines 2020. The protocol was registered with the international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews in health and social care (PROSPERO) (registration number CRD42019158079).

Selection criteria

The eligibility criteria were developed in accordance with the Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome (PICO) framework. The population were people with intellectual disabilities prescribed psychotropic medicines of any class for the management of behaviours that challenge. Studies that included adults or children with intellectual disabilities were included. Studies that included fewer than 50% of participants with intellectual disabilities or where data relating to those participants with intellectual disabilities were not reported separately were excluded. The focus of the intervention had to be deprescribing of psychotropic medicines. Studies conducted in both inpatient settings and community settings were eligible for inclusion. Community settings included residential care as well independent living supported by paid or unpaid carers. The primary outcomes were changes in behaviours that challenge and secondary outcomes were changes in quality of life measures or other outcomes such as mental health symptomatology (see Table 1).

Any experimental, quasi experimental, observational, or case report study reporting relevant quantitative data was included. For the synthesis, studies were grouped according to study design: randomised controlled trials, other comparison designs, pre post studies, longitudinal studies, and descriptive case reports. Studies reporting both individual participant-level data and summary data estimates were included. There were no restrictions on language or date of publication. We did not include abstracts and conference presentations.

Search strategy

Six electronic databases were searched: Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, CINAHL and Open Grey by the lead reviewer (DA) with a cut-off date of 21st August 2020 (see Table 2 for search strategy). Update searches were carried out on 14th March 2022 with one further case study identified for inclusion.

References were imported into an EndNote library, removing duplicates using both the software function and a manual check. Forwards and backwards reference searching of included papers was also conducted to track citations after the initial search and again after the updated search. Four key researchers, identified as having published several studies in this field over the last 10 years, were contacted to identify any further studies. Trial registries were not searched.

Data selection

Following the removal of duplicates, the titles and abstracts of the remaining records were reviewed by the primary reviewer (DA) against the eligibility criteria. A second reviewer (CS) undertook an independent screening of a random sample of 20% of abstract/title records. Following this, the remaining papers were subjected to full text screening by DA with another random sample of 20% of full texts screened by CS. Near perfect agreement was achieved for title /abstract screening (k = 0.86) and for full text screening (k = 0.81). Disagreements were resolved by discussion together with a third arbiter (PL). Automation tools were not used.

Data extraction

A bespoke data extraction form, consisting of six main categories with sub-categories, was developed to extract relevant data. The primary reviewer (DA) extracted data from all included studies and the second reviewer (CS) conducted independent data extraction for a random selection of 20% of studies. No formal agreement statistics were calculated but a high level of agreement was achieved.

Quality appraisal

Following data extraction, studies were individually appraised for risk of bias by DA using the appropriate tool from the Critical Appraisals Skills Programme Tools [16] each of which consist of ten questions to assess internal and external validity. Case reports and case series were quality appraised by using tool developed by Murad et al. [17]. The second independent reviewer (CS) quality appraised a random sample of 20% of the included studies, full agreement was reached.

Synthesis methods

Due to the heterogeneity of research design and the variability in participants, interventions and settings of included studies, a narrative approach was selected to synthesise the data, summarising the current evidence base in relation to the review question. Grouping the studies according to study design, the narrative synthesis focused on patterns in the direction and size of the effects of the deprescribing interventions and exploring relationships within and between studies and identifying factors that may help us to understand differences in reported findings [18].

Results

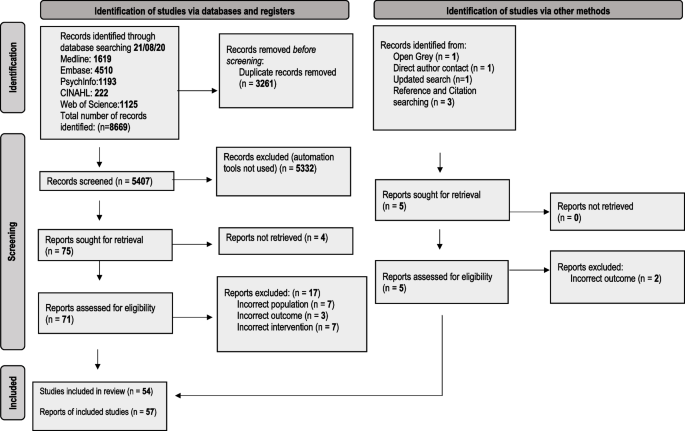

We identified 8675 records, and 57 reports relating to 54 studies met our eligibility criteria and were included in the review. This is reported in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1).

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for the deprescribing of psychotropic medicines in people with intellectual disabilities prescribed for behaviour that challenges: a systematic review [19]

Studies excluded at full text review together with reasons were recorded and listed in Table 3. Summary tables of extracted data for included studies are reported in Tables 4, 5, 6, and 7. A summary table of quality appraisal for included studies is reported in Table 8.

Included studies were carried out in nine countries, in both inpatient (n = 31) and community settings (n = 24). One study did not report setting.

Details of participant characteristics and numbers were incompletely reported in several studies, and in studies conducted by the same researchers, there was lack of clarity regarding duplication of participants [34, 37, 77].The total number of participants across all studies where reported was 3292. The percentage of participants reported to have severe/profound intellectual disabilities varied across study types ranging from 49% for RCTs, 62% for non-randomised controlled studies and 72% for pre post studies without randomisation control. One case study reported the participant to have severe/profound intellectual disabilities. Furthermore, the level of intellectual disability was incompletely or not reported in 33% of studies and the amount and type of support provided to participants was not reported in any of the studies. Ethnicity was reported in only five studies.

The most frequently deprescribed psychotropic medicines across all studies were typical and atypical antipsychotics. Aside from one RCT, the prescribing and administration of pro re nata (PRN) medication for the management of behaviours that challenge was incompletely reported [31].

Intervention approaches ranged from sudden discontinuation to gradually tapering dosage over 28 weeks. Sixteen studies reported the deprescribing intervention as integral to or supported by the wider multidisciplinary team [37, 38, 44, 46,47,48,49,50,51, 54, 55, 57, 65, 66, 75]. However, there were no data reported regarding working across organisation boundaries such as between primary and secondary care and no data reporting specific non pharmacological interventions to support deprescribing although for three studies the deprescribing interventions were in the context of a Positive Behaviour Support (PBS) framework [37, 38, 75]. Evidence of pharmacists working within the multidisciplinary team (MDT) was reported in 11 studies [37, 38, 44, 47, 49, 51, 54, 57, 60, 65, 75] and pharmacist non-medical prescribers delivering the interventions were reported in three studies, although the same pharmacist prescriber was involved in all three [37, 38, 75]. Follow up ranged from immediately after medication was reduced or discontinued to 15 years. For 22 studies, follow up was variable or not specified. Outcomes were measured using a range of standardised rating tools and questionnaires. Input from patients, carers, and family and models of co-production in developing multidisciplinary deprescribing interventions were not reported. The reporting of shared decision-making approaches involving patients, carers, and clinicians within deprescribing interventions were reported in three studies (all within a Positive Behavioural Support (PBS) framework) [37, 38, 75, 78]. Quality of Life outcomes were only reported in one pre post study [34] and one paper reporting three case studies [14].

Across all study types there was incomplete reporting of rates of complete psychotropic discontinuation, at least 50% psychotropic dose reduction, represcribing, behavioural changes and emergence of adverse effects. Where reported in RCTs using a tapering approach to deprescribing, rates of complete deprescribing ranged from 33 to 84% [20, 21, 23, 31, 32]. Relapse rates due to worsening of behaviour ranged from 62.5% to no worsening. In the non randomised group of studies, Gerrard et al. [37] reported up to 60% complete discontinuation with a further 50% achieving a 50% dose reduction with only one person requiring represcribing This contrasted to findings by Zuddas et al. [42] who reported that all three people who achieved discontinuation displayed behavioural deterioration requiring represcribing.

Randomised control trials (RCTs)

Seven RCTs evaluated the effects of deprescribing antipsychotic medicines [20, 21, 23, 30,31,32, 79], three on typical antipsychotics, three on atypical antipsychotics, and one on both types. Four studies were conducted in community settings [20, 23, 31, 32], two studies were carried out in an inpatient settings [30, 79] and one study included a mix of both [21]. Sample sizes ranged from 22 to 100 participants, with participant ages, where reported, ranging from 5 years to 78 years, with all 7 studies reporting outcomes for adults, 4 studies reporting outcomes for adolescents (ages 10--19 years [80]) and two studies reporting outcomes for children. The majority of participants were male ranging from 48 to 87% across RCTs. Length of follow up period varied from 4 weeks to 9 months following discontinuation or maximum dosage reduction. Primary outcome measures were firstly the changes in frequency and intensity of episodes of behaviours that challenge at follow up (we report follow up as time after planned complete discontinuation or maximum dosage reduction) and secondly, numbers of participants who reduced or stopped their antipsychotic medication.

Changes in behaviours that challenge

Assessment of the effects of deprescribing antipsychotics on behaviours that challenge was a primary outcome in all seven RCTs. Deprescribing antipsychotic medication was associated with a reduction in behaviours that challenge irrespective of whether the antipsychotic was tapered over 14 or 28 weeks in an RCT by de Kuijper et al. [23] This study involving 98 participants in community settings reported firstly that higher ratings of extrapyramidal and autonomic symptoms at baseline were associated with less improvement of behavioural symptoms after discontinuation; and secondly, higher baseline Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC) scores were associated with an increased likelihood of incomplete discontinuation [23].

Authors of studies where antipsychotic doses were reduced over 6 months [31] or 4 months [21] reported no clinically important changes in participants’ levels of aggression or behaviours that challenge at 9 months and 1 month respectively after planned discontinuation. Furthermore in a study by Ramerman et al. [32] study no change in irritability was reported when risperidone was reduced over 14 weeks in 86 participants compared to placebo.

In a study of the effects of withdrawal of zuclopentixol by Hassler et al. [79] behaviours that challenge increased at 12 weeks after sudden discontinuation of zuclopenthixol in 20 participants compared to the 19 participants that continued to be prescribed the antipsychotic. Heistad et al. [30] also reported increases in behaviours that challenge in participants undergoing deprescribing of thioridazine in a series of 5 separate groups within an RCT. Rates of relapse of behaviours that challenge were reported to be higher at 5 weeks follow up when risperidone was discontinued over 3 weeks in 38 adolescents and children in an RCT by the Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network research units [20]. Relapse rates were 62.5% for gradual placebo substitution and 12.5% for continued risperidone [20].

The deprescribing interventions of the three RCTs reporting overall increase in behaviours that challenge involved sudden discontinuation [30, 79] or tapering over the short time of 3 weeks. This compares to antipsychotics deprescribed over 14 to 28 weeks in studies reporting no change or a reduction in behaviours that challenge [21, 23, 31, 32]. In addition the follow up periods in the three RCTs [20, 30, 79] reporting increases in behaviours that challenge were shorter; 4 to 12 weeks compared to 4 weeks to 12 months in studies reporting no change or a reduction in behaviours that challenge [21, 23, 31, 32]. Two [30, 79] of the three RCTs reporting increases in behaviours that challenge were conducted in inpatient settings. Three [23, 31, 32] of the four studies reporting more favourable results regarding behaviours that challenge, were carried out in community settings, the fourth study [21] involving participants in both community and inpatient settings. The studies reporting less favourable effects on behaviours that challenges involved larger percentages of participants with severe or profound intellectual disabilities ranging from 34 to 72% [20, 30, 79]compared to 24 to 63% [23, 32] in two of the four studies reporting more favourable outcomes although two studies did not report level of intellectual disability [21, 31].

Reduction /discontinuation completion outcomes

Four studies [21, 23, 31, 32] used a study design involving tapering of the dose of antipsychotic dose three [21, 23, 32] of which reported numbers of participants achieving complete withdrawal.

Ahmed et al. [21] reported 33% of 36 participants achieved discontinuation with a further 19% achieving and maintaining at least a 50% reduction at one month follow up. de Kuijper et al. [23] reported 37% of 98 participants achieved complete discontinuation with significant improvements in behaviours that challenge at 12 weeks follow up. Secondly, they reported re-prescribing at follow up after an initially discontinuing in 7% of participants. Ramerman et al. [32] reported 82% of the 11 participants in the deprescribing group, completely withdrew from risperidone.

Other outcomes

Four studies reported outcomes of physical and mental health and wellbeing.

One study by de Kuijper et al. [24, 81] and another by Ramerman et al. [32] reported positive effects of deprescribing antipsychotics on physical health parameters. de Kuijpers et al. [24, 81] reported a mean decrease of 4 cm waist circumference, of 3.5 kg weight, 1.4 kg/m2 BMI, and 7.1 mmHg systolic blood pressure at 12 weeks follow up after planned discontinuation, in 98 participants following complete discontinuation of antipsychotics over 14 or 28 weeks. Ramerman et al. [32] reported favourable group time effects on weight, waist, body mass index, prolactin levels and testosterone levels in 11 participants who completely discontinued risperidone. However, this study was underpowered and follow up was limited to 8 weeks. Both complete discontinuation and dosage reduction of antipsychotics were reported by de Kuijper et al. [24] to lead to a decrease in prolactin plasma levels and an increase in levels of C- telopeptide type 1 collagen (CTX), the bone resorption marker [24]. Ahmed et al. [21] reported an association of typical antipsychotic reduction with increased dyskinesia. However the follow up time for this study was 4 weeks compared to the study by de Kuijper et al. [24]which had a follow up period of 12 weeks and the study by Ramerman et al. [32] which had an 8 week follow up period. Conversely, Hassler et al. [79] reported weight gain in participants who discontinued zuclopentixol [79] in an inpatient setting. Two [24, 32, 81] of the three studies reporting positive physical health outcomes were carried out in community settings and the third study [21] involved participants in both hospital and community settings.

Integrated synthesis of RCTs

The evidence from RCTs regarding the effects of deprescribing on behaviours that challenge at follow up was mixed. The length of follow up was inadequate for the majority of studies with four studies reporting follow up periods of between four and eight weeks [20,21,22, 30, 32] and a further two studies reporting follow up at 12 weeks [23, 24, 28, 79, 81] and therefore it could not be established if successful deprescribing could be maintained in those studies reporting positive effects or no change on behaviours that challenge.

The evidence suggests that discontinuing or reducing the dosage of antipsychotics can have positive effects on physical health such as the reversal of antipsychotic markers for metabolic syndrome. The several subclasses of antipsychotics and variable doses at baseline may limit the robustness of this evidence. Methodological limitations across all RCTs included the use of small sample sizes and limited reporting of information about blinding procedures and methods to ensure allocation concealment. Two studies did not make use of blinding [21, 23]. The treating physician was involved in the sampling and recruitment of participants in two RCTs leading to possible selection bias [21, 32].

Nonrandomised controlled studies

Seven nonrandomised controlled studies evaluated the effects of deprescribing antipsychotic medicines. Two studies were conducted in community settings [37, 42] and five studies were carried out in inpatient settings [35, 36, 39,40,41]. Sample sizes ranged from 6 to 80 participants, with participant ages, where reported, ranging from 7 years to 53 years, with 4 studies reporting outcomes for adults, one study reporting outcomes for adolescents (ages 10–19 years [80]) and one study reporting outcomes for children. The majority of participants were male ranging from 50 to 90% across studies. Length of follow up period varied from 8 weeks in one study to between 5 months and 12 months following discontinuation or maximum dosage reduction in those studies reporting. Two studies reported nonspecific variable follow up periods.

Behaviours that challenge

Two studies reported on changes in episodes or severity of behaviours that challenge. Zuddas et al. [42] reported progressive deterioration of behaviours in the 3 out of 10 adolescents and children participants who discontinued risperidone. A study by Swanson et al. [39] reported transient increases in ABC scores in 21 participants, 96% of whom had severe or profound intellectual disabilities, who discontinued risperidone and were co prescribed antiepileptic medication. However, this was not reported in the 19 participants who discontinued risperidone in the absence of antiepileptic medication.

Reduction /discontinuation outcomes

Two studies reported outcomes regarding numbers of participants who had their psychotropic medicines deprescribed. Zuddas et al. [42] reported that three children or adolescents discontinued risperidone although all three required the represcribing of an antipsychotic within 6 months following discontinuation.

A study by Gerrard et al. [37] comparing two groups of participants, reported a higher success rate for psychotropic medication reduction and discontinuation when this was carried out within a PBS framework. The authors reported that participants in the non-PBS group were more likely to have their medication increased following an initial reduction. Support was delivered by staff using a PBS framework for a minimum of three months post discontinuation or medication reduction. One patient required a medication increase or restart when supported by PBS. This compared to 66% of participants in the non-PBS group. However, evidence is limited by unequally matched groups in terms of intellectual disability [37] and the follow up times were variable.

Other outcomes

Four studies [35, 39,40,41] reported changes in dyskinesia scores following the deprescribing of antipsychotics. Aman and Singh [35] examined the effects of deprescribing typical antipsychotics on dyskinesias comparing a deprescribing group to a group that were not prescribed antipsychotics. The evidence was inconclusive although the deprescribing group was rated as having higher total dyskinesia scores.

Swanson et al. [39] reported transient increases in average Dyskinesia Identification System Condensed User Scale (DISCUS) scores after risperidone discontinuation with return to baseline 6 months after discontinuation. Wigal et al. [40] reported larger increases in DISCUS scores associated with greater dosage reductions of antipsychotics. Another study by the same authors measured the rates of dyskinesias during their medication review and dose reduction programme [41]. They reported that 63% of participants who discontinued antipsychotics and 29% of those who were receiving reduced dosages developed dyskinesias. In participants who were not medicated or where there was no change or increase in dosage, no dyskinesias were reported. All four studies were carried out in inpatient settings and most of the participants had severe or profound intellectual disabilities, ranging from 86 to 100%.

Pre post study designs

Twenty-seven pre-post studies evaluated the effects of deprescribing psychotropic medicines, with all studies reporting interventions involving antipsychotics and 6 studies reporting on interventions on more than one class of psychotropic medication [38, 46, 49,50,51, 55] including anxiolytics (n = 3), antidepressants (n = 4), sedatives/hypnotics (n = 2), benzodiazepines (n = 2), anticonvulsants (n = 1) and lithium (n = 2) in addition to antipsychotics [46, 49,50,51, 55, 77]. Eight studies were conducted in community settings,17 studies were carried out in inpatient settings, one study involved a mix of both, and one study did not report setting. Sample sizes ranged from 6 to 250 participants, with participant ages, where reported, ranging from 5 years to 84 years, with 14 studies reporting outcomes for adults, 6 studies reporting outcomes for adolescents (ages 10--19 years [80]) and one study reporting outcomes for children. The majority of participants were male ranging from 50 to 100% where reported. Length of follow up period varied from 8 weeks to 15 years following discontinuation or maximum dosage reduction with 12 studies reporting variable follow up or not reporting follow up periods.

Behaviours that challenge

From 12 studies reporting on the effects of deprescribing psychotropic medicines on behaviours that challenge the findings are mixed [33, 44, 46, 48, 52,53,54, 57,58,59, 61, 67]. Branford [44] reported no deterioration in behaviours that challenge in 25% of 123 participants who underwent a reduction of antipsychotics. However, 42% did show a deterioration in behaviours that challenge, and for 33%, changes in behaviour were not reported. de Kuijper et al. [33] reported at 16 weeks post planned discontinuation, 6% of participants had shown improvement and 9% had a worsening of behaviour; at 28 weeks, these percentages were 9 and 15%, and at 40 weeks 21 and 7%, respectively. They also concluded that at 28 weeks, those who had not achieved complete discontinuation had significantly more worsening of behaviour than those who had successfully discontinued. Ellenor et al. [46] reported ABS scores for 54 participants which showed a slight increase in behaviours that challenge for all three groups; medication reduced, medication stopped and control group. Fielding et al. [48] reported that all but eight of 68 participants whose antipsychotic medication was reduced, achieved permanent dosage reductions while maintaining rates of behaviours that challenge similar to those observed prior to deprescribing. They also found that behaviours that challenge decreased or remained stable for the majority although they slightly increased for some. In two studies by Janowsky et al. [52, 53] 40% of 138 participants with severe or profound intellectual disabilities and 96% of 49 participants with severe or profound intellectual disabilities were reported to experience a relapse in behaviours that challenge. Jauernig et al. [54] reported a lower frequency of behaviours that challenge at follow-up compared to baseline in all 3 patients (100%) whose antipsychotic had been discontinued and in 15 patients (79%) of 19 who underwent dose reduction. Luchins et al. [57] reported an improvement in behaviour associated with the reduction in prescribing of antipsychotics. Marholin et al. [58] reported reversible changes in behaviours that challenge when chlorpromazine was withdrawn suddenly and then restarted 23 days later in 6 participants with severe intellectual disabilities. Matthews and Weston [59]reported over 50% of 77 participants who were on regular thioridazine experienced behaviours that challenge during or following discontinuation. Adverse events were significantly associated with the duration of previous thioridazine prescription. May et al. [61] evaluated the effects of deprescribing risperidone in people with severe and profound intellectual disabilities and reported transient worsening of behaviours that challenge in 39%, persistent worsening in 39%, and progressive improvement in 22% of participants. Stevenson et al. [67] reported that 48.7% experienced onset or deterioration in behaviours or mental ill-health following the deprescribing of thioridazine.

Reduction /discontinuation outcomes

Nineteen studies [33, 38, 43, 44, 46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55, 57, 60, 65,66,67] reported lower prescribing rates, complete discontinuation, or reduced dosages of psychotropic medicines,14 of which reported an evaluation of a clinical service involving multidisciplinary medication reviews with varying time periods for follow up [38, 44, 46,47,48,49,50,51, 54, 55, 57, 60, 65, 66]. Nine of the studies reported evaluations of medication reviews involving pharmacists [38, 44, 46, 47, 49, 51, 54, 60, 65]. A medication review programme by Branford [44] reported 16% of 198 adult participants withdrawn from antipsychotics and 28% maintained on reduced dosage of antipsychotics at 12 months follow up. One hundred and twenty-three of the 198 participants underwent a reduction of their antipsychotics and 25% discontinued antipsychotics while 46% were receiving reduced dosages at 12 months follow up. Gerrard et al. [38] reported that 24 psychotropic medications were stopped within their retrospective study; 20 of these were with PBS support and ongoing deprescribing continued at the time of publication of the study in 2020. de Kuijper et al. [33] reported 61% had completely discontinued antipsychotics at 16 weeks, 46% at 28 weeks, and 40% at 40 weeks. However, 32 % of participants who initially withdrew at 16 weeks were represcribed antipsychotics at 28 weeks follow up and 13% who withdrew at 28 weeks were represcribed antipsychotics at 40 weeks follow up. Studies by Findholt et al. [49] and Howerton et al. [50] reported a decrease in polypharmacy. A retrospective review by Luchins et al. [57] reported the reduction of antipsychotic prescribing was associated with prescribing other psychotropic medicines such as carbamazepine, lithium, and buspirone.

Other outcomes

Nine studies [34, 38, 45, 56, 62,63,64,65, 67] reported physical health and wellbeing findings, one of which also reported mental health and wellbeing outcomes. Ramerman et al. [34] reported improved physical health amongst those who completely discontinued antipsychotics, while social functioning and mental wellbeing initially deteriorated in those who incompletely discontinued; however, this was temporary, and they recovered at 6 months after planned discontinuation. In addition, they reported that participants who had completely discontinued had temporary decreases in mental wellbeing. Similar findings were reported by de Kuijper et al. [45] who reported a positive association between complete antipsychotic discontinuation with less-severe parkinsonism and lower incidence of health worsening compared with participants with incomplete discontinuation. Shankar et al. [65] reported no placement breakdowns or hospital admissions following antipsychotic deprescribing at 3 months follow up. This contrasts to Stevenson et al. [67] who reported 12% of participants were admitted to psychiatric assessment and treatment unit and 8% of participants required increased carer support following deprescribing of thioridazine. Two studies reported weight loss following deprescribing; Linsday et al. [56] reported the weight of 14 children returned to baseline at 12 and 24 months following discontinuing risperidone and Gerrard [38] reported a reduction in weight gain following deprescribing. Newell et al. [62,63,64] reported transient withdrawal dyskinesia in three studies monitoring participants during the reduction of typical antipsychotics.

Integrated synthesis of non randomised controlled and pre post studies

The non randomised controlled studies and pre post studies, although they have less methodological rigour, offered similar evidence to the RCTs through their use of evaluations of clinical services and longer follow up periods. In addition, the non-randomised controlled studies report more extensively on dyskinesias. One non randomised controlled study [37] and 14 pre post studies [38, 44, 46,47,48,49,50,51, 54, 55, 57, 60, 65, 66] evaluated clinical services providing deprescribing interventions, making use of a multidisciplinary model rather than the traditional medical model when reducing medication. Studies by Gerrard et al. [37, 38] and a case study by Lee et al. [75] reported that deprescribing outcomes for a range of psychotropic medicines were more successful alongside PBS compared to patients undergoing deprescribing interventions without this framework.

The external validity of the pre post studies was limited due to their lack of control or comparison group which would have improved the methodology. Well over half (67%) were conducted in inpatient settings. However, the reporting of deprescribing of psychotropic medicines other than antipsychotics allows for some tentative conclusions about the de-prescribing of psychotropics other than antipsychotics. Outcome from these studies suggest that deprescribing interventions within a multidisciplinary model may be associated with successful outcomes in terms of reducing and discontinuing psychotropic prescribing which could be maintained over a longer-term basis.

Case studies

The effects of deprescribing on several classes of psychotropic medications were reported in 13 case studies [14, 68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76, 82] (3 separate case studies were reported in one paper). Five of these studies [14, 68, 75, 76] reported an association between successful discontinuation and improved quality of life. Another set of seven studies [69,70,71,72,73,74, 82] reported a range of adverse effects including delusions, hallucinations, inappropriate sexual behaviours, transient dyskinesias, self-harm, mania, aggression and catatonia following the deprescribing intervention. Lee et al. [75] described using flexible medication reduction within a PBS framework resulting in the discontinuation of risperidone.

Discussion

We are mindful that some studies included psychotropic medicines that are no longer prescribed e.g. thioridazine, and some are rarely prescribed e.g. chlorpromazine. However the focus of our review was the psychotropic deprescribing process rather than evidence of effectiveness of deprescribing individual medicines. Hence the findings from these studies will still be relevant and add to the evidence base of the effects of deprescribing psychotropic medicines in people with intellectual disabilities. Overall the evidence from RCTs indicated that deprescribing interventions for antipsychotic medicines prescribed for the management of behaviours that challenge in people with intellectual disabilities may lead to a reduction in dosage and may be discontinued under some circumstances. Reducing and discontinuing antipsychotics may have positive health outcomes on physical health parameters. This is particularly important in this population as people with intellectual disabilities experience health inequalities with more co morbidities and reduced life expectancy [83]. Findings demonstrating the successful reduction in dosage and discontinuation of psychotropic medicines was also found in the other study designs. Although of reduced methodological rigour, the longer follow up times and the inclusion of other classes of psychotropic medicines in addition to antipsychotics of these studies, added to the evidence base. However, these positive findings need to be considered in the context of a lack of high quality RCTs.

Negative effects of deprescribing should be acknowledged. Firstly, RCTs reported relapsing of behaviours that challenge, although this evidence is limited by variable periods of follow up, and secondly dyskinesias were reported by four non randomised controlled studies [35, 39,40,41] and three pre post studies [62,63,64]. Furthermore, initial deprescribing is sometimes reversed with the represcribing of psychotropic medicines at follow up and therefore caution is needed when synthesising evidence from studies with a wide range of follow up periods. A variety of reasons were given for represcribing which included increases in episodes and intensity of behaviours that challenge, restrictiveness of setting and staff training [21, 30]. Physical discomfort is associated with behaviours that challenges [84]. Evidence suggests that people with intellectual disabilities are more susceptible to movement side effects of antipsychotic drugs [85]. As dyskinesias may be exacerbated by discontinuation of psychotropic medication this raises concerns that tapers will sometimes be aborted due to irritability and agitation that may be secondary to discontinuation effects rather than a relapse of symptoms related to the medicine’s efficacy.

Aside from represcribing psychotropic medicines, outcomes regarding the consequences of relapsing behaviours that challenge such as placement breakdown, hospital admission and increase in required carer support was limited to two pre post studies [65, 67]. Lack of consensus regarding optimal follow up time periods was a consistent theme across all included studies affecting the heterogeneity of the methodologies. This impacted on synthesizing the evidence regarding positive outcomes.

Although the findings from our systematic review suggests that deprescribing interventions in people with intellectual disabilities prescribed psychotropic medication, may lead to dosage reductions and the discontinuation of these medicines, it remains unclear how to optimise the circumstances for this to take place.

However, despite the limitations to the evidence base, it seems likely that planning before initiating the deprescribing process may be helpful. This could include staff training to ensure that other interventions for any transient increases in behaviours that challenge can be optimised together with plans for addressing the emergence or the worsening of dyskinesias. The evaluation of stakeholder experiences to understand barriers and enablers of this process may provide clarity.

There is a large variation in clinical practice of prescribers regarding discontinuation of psychotropic medication, both in terms of the deprescribing process and the individuals who are identified as suitable for deprescribing, This may be partially related to environmental factors as setting culture and attitudes of staff towards off-label antipsychotic medication use in people with intellectual disabilities [86]. How these decisions are made will likely impact on the success of deprescribing interventions.

In summary our findings suggest it is likely that there may be several factors affecting successful outcomes of the psychotropic deprescribing process. Enablers of the deprescribing process may be the views and clinical practice of clinicians, embracing a multidisciplinary approach, pre-planning of the deprescribing process including how to address emergence or worsening of movement effects, availability and quality of staff training, and stakeholder attitudes, including those of the individuals who are prescribed these medicines, towards the deprescribing process. Barriers to this process may be the perceived negative effects of the deprescribing process, limited knowledge of discontinuation effects of the individual psychotropic medicines, lack of input from carers and lack of understanding of the experiences of people whose psychotropic medicines have been reduced. Our review found there was a lack of evidence in the literature of shared decision making between people with intellectual disabilities and the healthcare team. The lack of literature about quality of life is reflected in our review as we were unable to report extensively on this outcome.

Strengths and weaknesses of the methodology of included studies

With reference to reporting on medications, firstly, studies focused upon deprescribing one class or one specific type of medicine and did not address the co-prescribing of other psychotropic medicine, or an increase or decrease in dosage of these medicines. Secondly, studies did not report complete details regarding polypharmacy, where participants were co prescribed several medicines or were taking medicines available without prescriptions. This may have led to drug interactions and adverse drug reactions which could affect the outcomes of studies. Thirdly, the reporting of physical health medication and the prescribing and administration of PRN medication for the management of behaviours that challenge was missing from the included studies. Furthermore, there was frequent incomplete reporting of concurrent non-pharmacological treatments such as behavioural, psychological, and environmental interventions.

Strengths and weaknesses of the methodology of the systematic review

A weakness of our methodology was that the second reviewer was restricted to independently screening 20% of titles, abstracts and full text papers and extracting data from 20% of included studies due to limited resources. Within this review, we focused upon deprescribing all psychotropic medicines in people with intellectual disabilities, rather than just antipsychotics which has been previously examined [15]. The adverse effects and effects associated with discontinuation may vary between classes of psychotropic medicines and within classes. Further, it should be noted that while the inclusion of single case studies and retrospective studies allowed for a more inclusive synthesis of the literature, studies of this type are prone to bias.

Implications for clinicians and policymakers

Evidence based guidelines for prescribing psychotropic medicines in people with intellectual disabilities tend to focus on antipsychotics. There is a need to evaluate all psychotropic prescribing, including PRN, in people with intellectual disabilities to ensure that medication is being optimised and appropriate interventions are implemented within the multidisciplinary framework when addressing the management of behaviours that challenge.

We did not find evidence of involvement of patients, carers, and family within the development and process of deprescribing interventions. Whilst we have reported evidence suggesting that a multidisciplinary approach may be appropriate, policy makers and clinicians should be mindful to: (a) co-produce deprescribing interventions with people with intellectual disabilities to ensure they reflect their needs, which will, (b) help empower individuals to make informed decisions about their healthcare, and (c) facilitate full stakeholder engagement in shared decision making. It was noted that it was unclear as to how this was included within the intervention process within the included studies [14, 87, 88]. Co-production acknowledges that people with “lived experience” of using services are best placed to advise on what support and services will make a positive difference to their lives (Social Care Institute for Excellence, 2018).

Medicines optimisation is a patient centred framework forming part of routine clinical practice supporting patients to achieve best possible outcomes from their medicines by providing evidence based choices and ensuring medicines are as safe as possible [89]. Deprescribing should form part of medicines optimisation and incorporate routine monitoring to help improve health outcomes as evidence suggests that people with intellectual disabilities have poorer health outcomes [90]. Embracing a multidisciplinary approach and co-producing robust effective deprescribing processes with all stakeholders at the individual and service level may contribute to improved health outcomes reducing exposure to adverse effects. Routine monitoring within the medicines optimisation framework must address not only the effectiveness and adverse effects of medicines, but also discontinuation effects and possible relapses facilitating prompt medication review.

Implications for future research

Studies addressing quality of life measures would address the absence of this in the literature. We recommend that future research should focus on studies addressing confounding factors that we have highlighted above, namely the lack of reporting of other co-administered interventions. These interventions include the prescribing of other classes psychotropic medicines which were not the subject of the deprescribing intervention, the prescribing of PRN medication, psychological, environmental, and behavioural interventions. The length of the follow up period may have a significant impact on whether deprescribing can be deemed as successful in sustaining long term reduced reliance on psychotropic medication and temporary discontinuation effects and the re-emergence of behaviours that challenges. We therefore suggest longer follow up periods are needed within future studies. We also recommend that future research should also consider the feasibility of deprescribing all classes of psychotropic medicines in routine clinical practice in a range of settings, and with children, adolescents, and adults. Further studies of stakeholder experiences to identify enablers of deprescribing and best practice in involving people with intellectual disabilities and their carers in decisions about their medicines would be welcome. Recruitment and sampling challenges will need to be addressed in future research ensuring balance and reporting of age, gender, ethnicity, and level of intellectual disability within both inpatient and community settings. Further research to increase the knowledge of discontinuation symptoms of the various psychotropic medicines would be helpful when planning psychotropic deprescribing.

Further studies looking at enablers and barriers of the psychotropic deprescribing process, including addressing the impact of attitudes towards deprescribing of clinicians and carers on the success of deprescribing interventions, would be welcome as this could potentially influence initial decisions to implement deprescribing in individuals affecting outcomes.

Finally, it would be helpful if future studies exploring psychotropic deprescribing consistently reported outcomes regarding complete discontinuation, or greater dosage reduction, rate of represcribing, improvement and deterioration of behaviour and emergence of adverse effects.

Other information

Protocol and registration: The review protocol was registered on 19th December 2019 with PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews (registration number CRD CRD42019158079). https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42019158079.

Amended versions of the protocol were published on 7th July 2020, 17th September 2020, 30th September 2020 and 22nd March 2021. For further details regarding amendments please see link above.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study can be found in the summary table (Table 4), the quality assessment table (Table 5) and the raw data supplementary file (Table 8).

References

American Psychiatric Association D and Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Emerson E, Kiernan C, Alborz A, et al. The prevalence of challenging behaviors: a total population study. Res Dev Disabil. 2001;22:77–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0891-4222(00)00061-5.

Holden B, Gitlesen JP. A total population study of challenging behaviour in the county of Hedmark, Norway: prevalence, and risk markers. Res Dev Disabil. 2006;27:456–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2005.06.001.

Bowring DL, Totsika V, Hastings RP, et al. Challenging behaviours in adults with an intellectual disability: a total population study and exploration of risk indices. Br J Clin Psychol. 2017;56:16–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12118.

Emerson E. Challenging behaviour: analysis and intervention in people with severe intellectual disabilities. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001.

Excellence NIfHaC, editor. Challenging behaviour and learning disabilities: prevention and interventions for people with learning disabilities whose behaviour challenges [CG11]. Excellence NIfHaC, (ed.); 2015.

Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391:1357–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32802-7.

Barnes TR, Drake R, Paton C, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: updated recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2020;34:3–78.

Bowring DL, Totsika V, Hastings RP, et al. Prevalence of psychotropic medication use and association with challenging behaviour in adults with an intellectual disability. A total population study. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2017;61:604–17 Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't.

O'Dwyer M, Maidment ID, Bennett K, et al. Association of anticholinergic burden with adverse effects in older people with intellectual disabilities: an observational cross-sectional study. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209:504–10.

Owens DC. Tardive dyskinesia update: the syndrome. BJPsych Advances. 2019;25:57–69.

Cooper SJ, Reynolds GP, Wec-a, et al. BAP guidelines on the management of weight gain, metabolic disturbances and cardiovascular risk associated with psychosis and antipsychotic drug treatment. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:717–48.

Branford D, Gerrard D, Saleem N, et al. Stopping over-medication of people with intellectual disability, autism or both (STOMP) in England part 1-history and background of STOMP. Adv Ment Health Intellect Disabil. 2019;13:31–40. https://doi.org/10.1108/amhid-02-2018-0004.

Branford D, Gerrard D, Saleem N, et al. Stopping over-medication of people with an intellectual disability, autism or both (STOMP) in England part 2-the story so far. Adv Ment Health Intellect Disabil. 2019;13:41–51. https://doi.org/10.1108/amhid-02-2018-0005.

Sheehan R, Hassiotis A. Reduction or discontinuation of antipsychotics for challenging behaviour in adults with intellectual disability: a systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:238–56 Systematic Review.

(CASP). CASP. Critical appraisal skills Programme (CASP). https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/; 2015.

Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, et al. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid-Based Med. 2018:23.

Popay JRH, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, Britten N, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. ESRC Methods Programme. 2006.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906.

Risperidone Treatment of Autistic Disorder. Longer-term benefits and blinded discontinuation after 6 months. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1361–9.

Ahmed Z, Fraser W, Kerr MP, et al. Reducing antipsychotic medication in people with a learning disability. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:42–6 Clinical Trial Randomized Controlled Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't.

Smith C, Felce D, Ahmed Z, et al. Sedation effects on responsiveness: evaluating the reduction of antipsychotic medication in people with intellectual disability using a conditional probability approach. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2002;46:464–71 Evaluation Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't.

de Kuijper G, Evenhuis H, Minderaa RB, et al. Effects of controlled discontinuation of long-term used antipsychotics for behavioural symptoms in individuals with intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2014;58:71–83 Clinical Trial Multicenter Study.

de Kuijper G, Mulder H, Evenhuis H, et al. Effects of controlled discontinuation of long-term used antipsychotics on weight and metabolic parameters in individuals with intellectual disability. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33:520–4.

de Kuijper GM, Mulder H, Evenhuis H, et al. Effects of discontinuation of long-term used antipsychotics on prolactin and bone turnover markers in patients with intellectual disability. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;34:157–9.

de Kuijper GM, Hoekstra PJ. An open-label discontinuation trial of long-term, off-label antipsychotic medication in people with intellectual disability: Determinants of success and failure. J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;58:1418–26.

de Kuijper GM, Mulder H, Evenhuis H, et al. Effects of discontinuation of long-term used antipsychotics on prolactin and bone turnover markers in patients with intellectual disability. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;34:157–9 Letter Multicenter Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't.

Haessler F, Glaser T, Beneke M, et al. Zuclopenthixol in adults with intellectual disabilities and aggressive behaviours: discontinuation study. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:447–8 Multicenter Study Randomized Controlled Trial.

Hassler F, Glaser T, Reis O. Effects of zuclopenthixol on aggressive disruptive behavior in adults with mental retardation--a 2-year follow-up on a withdrawal study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44:339343 Multicenter Study.

Heistad GT, Zimmermann RL, Doebler MI. Long-term usefulness of thioridazine for institutionalized mentally retarded patients. Am J Ment Defic. 1982;87:243–51 Clinical Trial Controlled Clinical Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.

McNamara R, Randell E, Gillespie D, et al. A pilot randomised controlled trial of community-led ANtipsychotic drug REduction for adults with learning disabilities. Health Technol Assessm (Winchester, England). 2017;21:1–92 Randomized Controlled Trial.

Ramerman L, de Kuijper G, Scheers T, et al. Is risperidone effective in reducing challenging behaviours in individuals with intellectual disabilities after 1 year or longer use? A placebo-controlled, randomised, double-blind discontinuation study. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2019;63:418–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12584.

de Kuijper GM, Hoekstra PJ. An open-label discontinuation trial of long-term, off-label antipsychotic medication in people with intellectual disability: determinants of success and failure. J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;58:1418–26 Clinical Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't.

Ramerman L, Hoekstra PJ, Kuijper G. Changes in health-related quality of life in people with intellectual disabilities who discontinue long-term used antipsychotic drugs for challenging behaviors. J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;59:280–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcph.1311.

Aman MG, Singh NN. Dyskinetic symptoms in profoundly retarded residents following neuroleptic withdrawal and during methylphenidate treatment. J Ment Defic Res. 1985;29:187–95.

Carpenter M, Cowart CA, McCallum RS, et al. Effects of antipsychotic medication on discrimination learning for institutionalized adults who have mental retardation. Behavior Resident Treatm. 1990;5:105–20.

Gerrard D, Rhodes J, Lee R, et al. Using positive behavioural support (PBS) for STOMP medication challenge. Adv Ment Health Intellect Disabil. 2019;13:102–12. https://doi.org/10.1108/AMHID-12-2018-0051.

Gerrard D. Delivering STOMP in a community learning disability treatment team hospital pharmacy Europe; 2020.

Swanson JM, Christian DL, Wigal T, et al. Tardive dyskinesia in a developmentally disabled population: manifestation during the initial stage of a minimal effective dose program. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;4:218–23.

Wigal T, Christian DL, Wigal SB, et al. Classification of types of tardive dyskinesia in a developmentally disabled population at a public residential facility. J Dev Phys Disabil. 1993;5:55–69.

Wigal T, Swanson JM, Christian DL, et al. Admissions to a public residential facility for individuals with developmental disabilities: change in neuroleptic drug use and tardive dykinesia. J Dev Phys Disabil. 1994;6:115–24.

Zuddas A, Di Martino A, Muglia P, et al. Long-term risperidone for pervasive developmental disorder: efficacy, tolerability, and discontinuation. J Child Adoles Psychopharmacol. 2000;10:79–90 Clinical Trial.

Brahm NC, Buswell A, Christensen D, et al. Assessment of QTc prolongation following thioridazine withdrawal in a developmentally disabled population. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23:314–5 Letter.

Branford D. A review of antipsychotic drugs prescribed for people with learning disabilities who live in Leicestershire. J Intellect Disabil Res. 1996;40:358–68.

de Kuijper GM, Hoekstra PJ. An open label discontinuation trial of long-term used off-label antipsychotic drugs in people with intellectual disability: the influence of staff-related factors. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2019;32:313–22 Clinical Trial.

Ellenor GL, Frisk PA. Pharmacist impact on drug use in an institution for the mentally retarded. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1977;34:604–8 Research Support, U.S. Gov't, Non-P.H.S.

Ferguson DG, Cullari S, Davidson NA, et al. Effects of data-based interdisciplinary medication reviews on the prevalence and pattern of neuroleptic drug use with institutionalized mentally retarded persons. Educ Train Menta Retard. 1982;17:103–8.

Fielding LT, Murphy RJ, Reagan MW, et al. An assessment program to reduce drug use with the mentally retarded. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1980;31:771–3 Comparative Study.

Findholt NE, Emmett CG. Impact of interdisciplinary team review on psychotropic drug use with persons who have mental retardation. Ment Retard. 1990;28:41–6.

Howerton K, Fernandez G, Touchette PE, et al. Psychotropic medications in community based individuals with developmental disabilities: observations of an interdisciplinary team. Mental Health Aspects Dev Disabil. 2002;5:78–86.

Inoue F. A clinical pharmacy service to reduce psychotropic medication use in an institution for mentally handicapped persons. Ment Retard. 1982;20:70–4.

Janowsky DS, Barnhill LJ, Khalid AS, et al. Relapse of aggressive and disruptive behavior in mentally retarded adults following antipsychotic drug withdrawal predicts psychotropic drug use a decade later. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1272–7 Comparative Study.

Janowsky DS, Barnhill LJ, Khalid AS, et al. Antipsychotic withdrawal-induced relapse predicts future relapses in institutionalized adults with severe intellectual disability. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:401–5 Multicenter Study.

Jauernig R, Hudson A. Evaluation of an interdisciplinary review committee managing the use of psychotropic medication with people with intellectual disabilities. Austr New Zealand J Dev Disabil. 1995;20:51–61.

LaMendola W, Zabaria ES, Carver M. Reducing psychotropic drug use in an institution for the retarded. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1980:31.

Lindsay RL, Leone S, Aman MG. Discontinuation of risperidone and reversibility of weight gain in children with disruptive behavior disorders. Clin Pediatr. 2004;43:437–44.

Luchins DJ, Dojka DM, Hanrahan P. Factors associated with reduction in antipsychotic medication dosage in adults with mental retardation. Am J Ment Retard. 1993;98:165–72 Comparative Study.

Marholin D 2nd, Touchette PE, Stewart RM. Withdrawal of chronic chlorpromazine medication: an experimental analysis. J Appl Behav Anal. 1979;12:159–71 Clinical Trial Controlled Clinical Trial.

Matthews T, Weston SN. Experience of thioridazine use before and after the committee on safety of medicines warning. Psychiatr Bull. 2003;27:87–9.

Marcoux AW. Implementation of a psychotropic drug review service in a mental retardation facility. Hosp Pharm. 1985;20:827–31.

May P, London EB, Zimmerman T, et al. A study of the clinical outcome of patients with profound mental retardation gradually withdrawn from chronic neuroleptic medication. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1995;7:155–60.

Newell KM, Bodfish JW, Mahorney SL, et al. Dynamics of lip dyskinesia associated with neuroleptic withdrawal. Am J Ment Retard. 2000;105:260–8 Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.

Newell KM, Wszola B, Sprague RL, et al. The changing effector pattern of tardive dyskinesia during the course of neuroleptic withdrawal. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;9:262–8 Clinical Trial Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.

Newell KM, Ko YG, Sprague RL, et al. Onset of dyskinesia and changes in postural task performance during the course of neuroleptic withdrawal. Am J Ment Retard. 2002;107:270–7 Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.

Shankar R, Wilcock M, Deb S, et al. A structured programme to withdraw antipsychotics among adults with intellectual disabilities: the Cornwall experience. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2019;32:1389–400.

Spreat S, Serafin C, Behar D, et al. Tranquilizer reduction trials in a residential program for persons with mental retardation. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1993;44:1100–2.

Stevenson C, Rajan L, Reid G, et al. Withdrawal of antipsychotic drugs from adults with intellectual disabilities. Ir J Psychol Med. 2004;21:85–90.

Adams D, Sawhney I. Deprescribing of psychotropic medication in a 30-year-old man with learning disability. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2017;24:63–4.

Bastiampillai T, Fantasia R, Nelson A. De novo treatment-resistant psychosis following thioridazine withdrawal. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48:585–6.

Brahm NC, Fast GA. Increased sexual aggression following ziprasidone discontinuation in an intellectually disabled adult man. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psych. 2009;11:361.

Connor DF. Stimulants and neuroleptic withdrawal dyskinesia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:247–8.

Dillon JE. Self-injurious behavior associated with clonidine withdrawal in a child with Tourette's disorder. J Child Neurol. 1990;5:308–10.

Faisal M, Pradeep V, O'Hanrahan S. Case of paediatric catatonia precipitated by antipsychotic withdrawal in a child with autism spectrum disorder. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(4):e240785.

Ghaziuddin N, Ghaziuddin M. Mania-like reaction induced by benzodiazepine withdrawal in a patient with mental retardation. Can J Psychiatr Rev Can Psychiatr. 1990;35:612–3 Case Reports.

Lee RM, Rhodes JA, Gerrard D. Positive Behavioural support as an alternative to medication. Tizard Learn Disabil Rev. 2019;24:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1108/tldr-06-2018-0018.

McLennan JD. Deprescribing in a youth with an intellectual disability, autism, behavioural problems, and medication-related obesity: a case study. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;28:141–6.

Gerrard D. Delivering STOMP in a community learning disability treatment team hospital pharmacy Europe; 2019.

Gore NJ, McGill P, Toogood S, et al. Definition and scope for positive behavioural support. Int J Positive Behavioural Support. 2013;3:14–23.

Hassler F, Glaser T, Pap AF, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled discontinuation study of zuclopenthixol for the treatment of aggressive disruptive behaviours in adults with mental retardation - secondary parameter analyses. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2008;41:232–9 Multicenter Study Randomized Controlled Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't.

Organisation WH. Adolescent health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health. Accessed 14 Mar 2022.

de Kuijper G, Mulder H, Evenhuis H, et al. Effects of controlled discontinuation of long-term used antipsychotics on weight and metabolic parameters in individuals with intellectual disability. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33:520–4 Clinical Trial Multicenter Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't.

Valdovinos MG, Ellringer NP, Alexander ML. Changes in the rate of problem behavior associated with the discontinuation of the antipsychotic medication quetiapine. Mental Health Aspects Dev Disabil. 2007;10:64–7.

Emerson E, Baines S, Allerton L, et al. Health inequalities and people with learning disabilities in the UK; 2011.

Challenging behaviour: a unified approach. Psychiatr Bull. 2007;31:400–0. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.31.10.400.

Sheehan R, Horsfall L, Strydom A, et al. Movement side effects of antipsychotic drugs in adults with and without intellectual disability: UK population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017406. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017406.

de Kuijper GM, Hoekstra PJ. Physicians' reasons not to discontinue long-term used off-label antipsychotic drugs in people with intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2017;61:899–908. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12385.

Adams D, Carr C, Marsden D, et al. An update on informed consent and the effect on the clinical practice of those working with people with a learning disability. Learn Disabil Pract. 2021;24.

Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality. London: King's Fund; 2011.

Duerden MAT, Payne R. Polypharmacy and medicines optimisation: The King's Fund; 2013.

Heslop P, Calkin R, Byrne V. The learning disabilities mortality review (LeDeR) Programme: annual report 2019. University of Bristol, Norah Fry Centre for Disability Studies; 2020.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DA, RH, IM and PL have made substantial contributions to the conception and design of this systematic review. DA and CS have made substantial contributions to the acquisition of data. DA and CS have made substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data. DA wrote the main manuscript with input from RH, IM and PL. DA, RH, IM, CS and PL have approved the submitted version and to have agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Adams, D., Hastings, R.P., Maidment, I. et al. Deprescribing psychotropic medicines for behaviours that challenge in people with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 23, 202 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04479-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04479-w